The Duellists (1977)

Director: Ridley Scott

Reviewed by Roderick Heath

Sir Ridley Scott today stands at the forefront of popular cinema with a raft of famous films and also a slew of failures. Scott rode at the vanguard of a generation of British film-makers who stressed a powerful visual style, some trained in television and advertising, many of whom found varying degrees of success in Hollywood. Scott and others owed their chance to impresario producer David Puttnam, who led an ill-fated but impressive campaign by British cinema to reconstitute itself as a global force after a collapse in the early '70s. The Duellists, an opening shot in the campaign, was a Cannes Camera D’Or winner and gained Scott enough attention to land him the job of directing Alien.

For me, his masterpiece is still his debut. As in his best works, it concentrates on a fierce conflict (a common theme, in variations, with Alien, Blade Runner, 1492: The Conquest of Paradise, Thelma and Louise, Gladiator, Black Hawk Down, and Kingdom of Heaven). It is obviously influenced by Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon in evoking with the texture of still life and landscape paintings of the eighteenth century, and by turning a swashbuckling story inside out by its cool style to become a study in irony. Yet it is its own film and possibly a superior one. At first glance, The Duellists seems disjointed, episodic. We see two men encounter each other at various points in the 15-year campaign across Europe by Napoleon's Grande Army. The film's "chapters," identified by locale and date, convey a sense of the toll of war as friends and faces appear, make their indelible impression, and are lost and forgotten. In this way, The Duellists manages at once to maintain the precision of a short story but also evoke a novel’s expanse.

The narrative, adapted from a Joseph Conrad tale drawn from an apparently true account, begins in Strasbourg in 1800, “the year Napoleon Bonaparte became ruler of France” as Stacy Keach’s narration puts it. Gabriel Feraud (Harvey Keitel, in one of his habitu

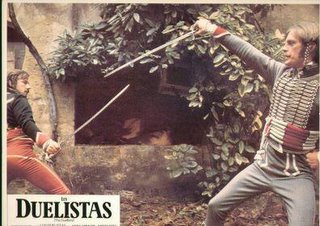

ally terrific performances in unexpected parts), a lieutenant in the 7th Hussars, happily skewers the nephew of the town’s mayor in a duel because the man insulted Bonaparte. The formidable General Treillard (Robert Stephens, the first in the film’s pitch-perfect character turns), enraged, orders D’Hubert, a talented young lieutenant (Keith Carradine, whose spindly charm is odd but effective), to find Feraud and place him under house arrest. He finds Feraud at the salon of Madame de Lionne (Jenny Runacre). On their way to Feraud’s billet, D’Hubert trips verbally over Feraud’s fuming, until Feraud directs his rage at D’Hubert and demands satisfaction. Their duel is interrupted when D’Hubert slashes Feraud’s arm, causing Feraud’s mistress (Gay Hamilton) to assault him.

ally terrific performances in unexpected parts), a lieutenant in the 7th Hussars, happily skewers the nephew of the town’s mayor in a duel because the man insulted Bonaparte. The formidable General Treillard (Robert Stephens, the first in the film’s pitch-perfect character turns), enraged, orders D’Hubert, a talented young lieutenant (Keith Carradine, whose spindly charm is odd but effective), to find Feraud and place him under house arrest. He finds Feraud at the salon of Madame de Lionne (Jenny Runacre). On their way to Feraud’s billet, D’Hubert trips verbally over Feraud’s fuming, until Feraud directs his rage at D’Hubert and demands satisfaction. Their duel is interrupted when D’Hubert slashes Feraud’s arm, causing Feraud’s mistress (Gay Hamilton) to assault him. The only similarity between Armand D’Hubert and Gabriel Feraud is that both are exceptionally good, brave soldiers. Armand's efforts are to be rational, reasonable, and he gives competent, intelligent commands. But he is a man who does not understand himself. His self-description, “I’m a temperate man!" is rightly laughed at. His strength of character proves at odds with - and better than - his surface and self-opinion. He cannot be seen to turn tail, or to tell tales, although he considers the quarrel incoherent. D’Hubert has the kind of guts that arise from necessity. Feraud relishes violence. Armand’s physician friend Jacquin (Tom Conti), in considering Feraud’s face, describes perfectly one kind of bigot: "The enemies of reason have a certain blind look." For Feraud, casual provocations disguise deep private resentments, and his psyche feeds on hate. He refers to Armand as a “boudoir soldier” and “staff lackey” where he himself is “man who would ride straight at anything”, a lad who spends his time boozing, screwing and betting. The duel is more than a point of honor; it is his extreme sport, the thing that stirs his blood and gives a mode of self-expression. “You make fighting a duel sound like a pastime in the Garden of Eden!” Armand comments, and finds, for Gabriel, it's true. It is a point of mocking frustration that he cannot destroy a man he considers so weak.

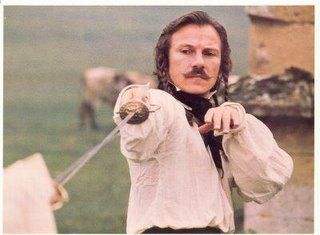

Armand’s mistress is the intensely sexual, sprightly, but subtly melancholy Laura (Diana Quick). She has a standing marriage proposal she passed up to be with Armand, “the only one I ever loved”, when she comes across him in Augsburg. Laura keeps account of her fellow vivandieres and the soldiers they loved, and is used to living with death, maiming, and ruination not as a gallant hussar but as a passive ledger-keeper, the price paid for bathing in soldiers' sexy, spectacular glory. In a second, swift set-to, Armand receives a gash in his chest. Feraud will not shake hands. Armand grows intent and distant ("It takes all one's attention to be ready"), and Laura's love is worn down by the tension. Laura subsequently confronts Feraud in his tent to size him up. He jokingly draws a sword for protection, saying, “I once knew a man who was stabbed by a woman; it gave him the surprise of his life.” She ripostes, “I once knew a woman who was beaten to death by a man. I don’t think it surprised her at all.” Finally, Laura leaves Armand with a pointed message, “Good-bye,” written in lipstick on his saber. In barren despair, Armand throws himself into a brutal match with Feraud where the two men end up wrestling in utter exhaustion on the ground.

Despite the harm to his personal life and the tirades he receives from Gen. Treillard, Armand benefits from his reputation as a “notorious and savage duelist,” as his pal Lacourbe (Alun Armstrong) jests, “All the little girls adore you." Indeed, these soldiers hold the dazzling, outside-the-common status held only for rock and film stars today. Their dueling is considered grand theatre and entertainment. Their next fight, in Lubeck, 1806, is done on horseback, as “a compliment to the cavalry.” Before it, Armand encounters Laura once more; having married and lost her suitor in a typhus epidemic, she has returned as a bitter wretch whom Armand urges to go home. She spitefully hisses, "This time he'll kill you!", which is indeed Armand's belief. As the two men face off on their chargers, and race in for the kill, Scott makes an inspired stylistic shift; a series of flash cuts illuminates Armand’s realizing the evil mark Feraud has left on his life. Armand gains warrior rage and leaves his enemy with his scalp peeled back from his head.

“Six years later," Keach intones, “The Emperor’s Grand Army regrouped for Armageddon.” “Russia, 1812” glimpses grim destruction of a gallant band, who, bitten by frost, starved, without boots, almost inhuman, drag themselves across a frigid landscape. When he catches sight of D'Hubert, Feraud bunks down with two rifles in paranoia even as they huddle and shiver in a blizzard. Against all the codes they have been following, they duel in private. They are only stopped by the intrusion of Cossacks who mock them, and the two men fight off their mutual enemy. Feraud, comfortably animalistic, calmly slices a wounded Cossack’s throat and refuses D’Hubert’s offer of a drink. D’Hubert finds Lacourbe’s frozen, ice-sheathed body, a haunting image of lonely death on the edge of nothingness - and a shot tellingly quoted in Scott's most recent film, Kingdom of Heaven.

“Tours, 1814” finds D’Hubert, retired at the rank of general, living at his sister Leonie's (Meg Wynn Owen) estate, nursing a wounded leg, telling his nephews war stories. Leonie, recognizing the danger and waste of his want to retire from life, sets about matchmaking Armand with the niece of a neighboring Chevalier (Alan Webb), who is happy to be restored to rank but also fussily proud of his acquired trade as a boot-maker. Armand’s romance with Adele (Christina Raines) regenerates him from emaciated, limping burn-out to an ardent lover and serving commander. Bonaparte’s escape from Elba brings ghosts back to his door. A colonel (Edward Fox) brings D’Hubert the offer of a command: “The Emperor is our strength. We belong to him.” “I rather fancied I belonged to myself,” Armand answers icily. Though still insistent on honor and integrity, Armand has rejected grand projects and ethereal ethics. After Waterloo Feraud and his fellows return as glowering, misshapen stumps of men, whilst D’Hubert grows strong, rich, secure, with a command under the King, and expecting a child by his beautiful bride.

In "Paris, 1816," Armand approaches Fouché (Albert Finney), a "virtuoso of survival," a turncoat who has gotten the job of handling political prisoners, to save Feraud from the chopping block, an interference he requests be kept secret. We sense Armand’s personal code of honor will not allow him the shabby security of letting Feraud be taken care of by someone else. Yet we also suspect Armand hopes to settle unfinished business and take on the ugly accusations of the Bonapartists, even as when Feraud, embalmed in imitation of his exiled idol, comes looking for his nemesis, Armand condemns the proposed duel as a farce. Their final encounter, enacted around a ruined castle in a pristine morning wood, sees Feraud’s raw hunter’s cunning almost victorious, but Armand’s wits clinch the moment. As he aims his gun at the goading Feraud, we suddenly leave the scene behind, and next see Armand proceeding home, greeting his worried wife with cheer. And Feraud? We return to him, wandering the woods musing on Armand's declaration, “By every rule of single combat from this moment your life belongs to me, is that not correct? Then I shall simply declare you dead. In all your dealings with me you do me the courtesy to conduct yourself as a dead man. I have submitted to your notions of honor long enough. You will now submit to mine.” Armand no longer plays by Feraud’s bloodthirsty ethic, but his own, as a man of sense who lives and grows. Our last glimpse of Feraud shows him overlooking a flooded valley in a sun-shower. The scene before him would lift most men to a sense of glory - but the final shot, closing in on his implacable, brooding face, shows he is doomed to sink inwards in gravely gnawing spite.

Beyond being a relevant study of a peculiar kind of masculine madness that is most certainly not dead although the mode it expresses itself in here - the duel - is long defunct, The Duellists provides a map for the greatness and failure of the Napoleonic movement in specific and militarism in general; liberating, beautiful, stimulating, monstrous, destructive, dead-ended. Gerald Vaughn-Hughes’ screenplay is a model of subtlety and wit, and Scott’s direction is sublime illustration. None of his later films have scripts as good nor such rigorous control (born partly out of necessity to reduce costs). At times Scott serves up overly-arch shots designed merely to awe with their prettiness. However, the film’s enormous sensual beauty does not weigh it down, and Scott employs hand-held cameras and jump cuts with creative fidelity to the evocation of an inherently more physical age. Cinematographer Frank Tidy is alive to every blade of grass, belt buckle and bead of water. As a last note on the film’s fusion of technical and artistic skill, Howard Blake’s score is a little masterpiece in itself. l

Roderick Heath is an author, poet, and film geek living in the lustrous Blue Mountains outside Sydney, Australia.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home