A Man Escaped (Un condamné à mort s'est échappé) (1956)

A Man Escaped (Un condamné à mort s'est échappé) (1956)Director: Robert Bresson

A Man Escaped, one of my all-time favorite films, is a singular experience. How does a film whose title tells you how it ends still manage to be one of the most suspenseful films ever made? It's not easy to articulate, but I'll try.

The source material certainly has built-in drama. The film is based on a book by André Devigny, a WWII French Resistance fighter, who escaped from Fort Montluc prison in Lyon, France, where the Gestapo held political prisoners awaiting trial and execution. Indeed, a more accurate translation of Bresson's title is "A Condemned Man Escaped." Bresson's adaptation clings very closely to the details of Devigny's account and was filmed in Montluc itself, thereby creating an almost unbearable suspense by nearly recreating the experience.

Then, of course, there is Bresson's artistry in using small, closely observed moments built up meticulously to place viewers in the position of a prisoner of the Gestapo

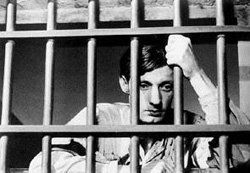

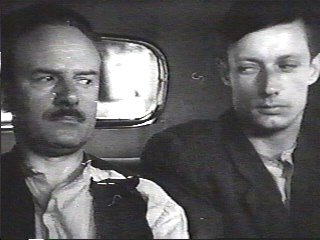

. Consider the opening, which perfectly sets the tone for the entire film. Fontaine (François Leterrier), the condemned man of the title, is riding in the back seat of a car, his wrists handcuffed together. His eyes shift warily above his angular face framed with loose, dark hair. The camera shifts several times from his face to his hands, which move tentatively on and off the door handle. The car slows and Fontaine seizes his chance. We watch him suddenly push the handle all the way down and fly out the door. Yells and scuffling (was there a shot?) follow. Moments later, we are inside the car again and watch as Fontaine is shoved back in. This time, his guard handcuffs himself to Fontaine. When Fontaine reaches the prison, his escape attempt is conveyed to the commandant. When next we see Fontaine, he is being carried into a cell. Bloodied and unconscious, he is dumped unceremoniously inside the cell. We hear a key turn heavily in the lock. At this point, voiceover narration from inside Fontaine's mind is added to the sparse dialogue that propels the story.

. Consider the opening, which perfectly sets the tone for the entire film. Fontaine (François Leterrier), the condemned man of the title, is riding in the back seat of a car, his wrists handcuffed together. His eyes shift warily above his angular face framed with loose, dark hair. The camera shifts several times from his face to his hands, which move tentatively on and off the door handle. The car slows and Fontaine seizes his chance. We watch him suddenly push the handle all the way down and fly out the door. Yells and scuffling (was there a shot?) follow. Moments later, we are inside the car again and watch as Fontaine is shoved back in. This time, his guard handcuffs himself to Fontaine. When Fontaine reaches the prison, his escape attempt is conveyed to the commandant. When next we see Fontaine, he is being carried into a cell. Bloodied and unconscious, he is dumped unceremoniously inside the cell. We hear a key turn heavily in the lock. At this point, voiceover narration from inside Fontaine's mind is added to the sparse dialogue that propels the story. Fontaine's further experiences are built up with equal care. He learns the tapping method prisoners use to communicate with each other through their cell walls. By examining the walls of his cell, he finds a means to look out his high cell window. He observes three prisoners walking up and down the exercise quad and stage-whispers to them about the possibility of getting a message out to his comrades. The risks of trusting anyone in this regimented setting where nearly every movement is observed are made glaringly

Fontaine's further experiences are built up with equal care. He learns the tapping method prisoners use to communicate with each other through their cell walls. By examining the walls of his cell, he finds a means to look out his high cell window. He observes three prisoners walking up and down the exercise quad and stage-whispers to them about the possibility of getting a message out to his comrades. The risks of trusting anyone in this regimented setting where nearly every movement is observed are made glaringly clear. People appear and disappear, their fates known only by a quick sentence from one prisoner to another--or not at all. Notes pass surreptitiously between prisoners as they conduct their toilet. The furtiveness of each movement, the uncertainty of what each day will bring, the ever-present blood stains on Fontaine's only shirt, put there by his initial beating--all these reminders of danger and death persist in our view.

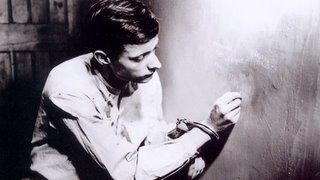

clear. People appear and disappear, their fates known only by a quick sentence from one prisoner to another--or not at all. Notes pass surreptitiously between prisoners as they conduct their toilet. The furtiveness of each movement, the uncertainty of what each day will bring, the ever-present blood stains on Fontaine's only shirt, put there by his initial beating--all these reminders of danger and death persist in our view.Certain of execution, Fontaine hatches an escape plan. He notices a weakness in the boards of his wooden cell door. Saving a spoon off his meal tray, he hones its handle on the rough stones of his cell floor into a chisel to remove the boards. His neighbor, despairing and normally uncommunicative, tells him as they talk at their cell windows that Fontaine will get them all killed with his scratching. Fontaine tells his comrade to have courage. In this subtle way, Bresson introduces a theme that he will revisit from many angles in many of his later films--irrepressible fate resisted through faith and persistence. Indeed, Bresson adds a secondary title to his adaptation, Le vent souffle où il veut. Dona nobis pacem. Translated, it means The Wind Bloweth Where It Listeth. Give Us Peace.

At last, Fontaine, having methodically tested his escape plan and assembled his homemade tools, must make his move. At that very moment, a young man (Charles Le Clainche) wearing a jacket from a German uniform is placed in his cell. Fontaine either must take Jost along or kill him. The tension of this moment, the gravity of his dilemma, are almost too much to bear. The actual escape juxtaposes silence with potentially lethal noise--a slipping tile on the roof, an unidentified squeaking in the yard separating the inner and outer walls of the prison. Bresson is famous for his use of sound. His mastery was never more apparent than in this film, where sound often must substitute for sight for prisoners cut off from ordinary life.

This film, like most Bresson films, rewards close attention. In fact, it would be hard to watch without fixing all one's senses to it. In this distracted age, Bresson is not an easy director to warm up to. He is, however, one of the greatest directors who ever lived, and one who grapples with difficult, but important subjects of the human spirit. I hope you will seek out his works and come to love them as I do. l

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home