Dancing at Lughnasa (1998)

Dancing at Lughnasa (1998)Director: Pat O’Connor

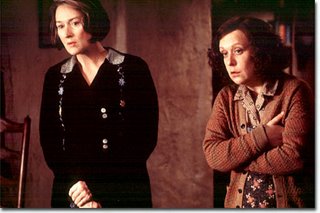

Playwright Brian Friel is a delicate conjurer of Irish life and lore. His plays show a particular regard for language, the effects of emigration from Ireland, British colonization of the island, and memory as reflected through the prism of individuals who seem to be moved by forces beyond their control—especially love. Dancing at Lughnasa, a drama about the five unmarried Mundy sisters of County Donegal, is Friel’s most successful play. The movie that was made of it, starring Meryl Streep as Kate, the overbearing eldest sister, does not carry the patented Friel tone of rueful sweetness. Instead, it opts for a Brechtian distance that, while bearing its own rewards, seems misplaced in a country as deeply sentimental as Ireland.

The story is told in flashback (narrated Gerard McSorley) as Michael remembers the magical summer of 1937 when he was a boy (Darrell Johnston) awaiting the return of his uncle Jack (Michael Gambon), a priest who has spent 25 years in Uganda. Michael is the illegitimate son of youngest sister Christina (Catherine McCormack). That same summer, Michael's mostly absent father, a restless, attractive Welshman named Gerry Evans (Rhys Ifans), also returns to the Mundy household to say good-bye before he is off on his latest adventure fighting against Franco in Spain.

Michael recalls his aunts with shorthand description. Where Kate is all prim propriety and prohibition—the perfect spinster schoolteacher—Maggie (Kathy Burke) is lively, outspoken, and

Michael recalls his aunts with shorthand description. Where Kate is all prim propriety and prohibition—the perfect spinster schoolteacher—Maggie (Kathy Burke) is lively, outspoken, and  raffishly smokes cigarettes. Christina is a romantic, a beauty on the way to losing both her looks and her free spirit when she eventually succumbs to the drudgery of factory work. Agnes (Brid Brennan) is quiet; still waters run deep, says Michael. Rose (Sophie Thompson) is simple-minded and slow. That would imply that she is mildly retarded, but she doesn't really seem so. Each sister plays her role in maintaining the balance in the Mundy household, with Kate reigning supreme. But even her iron will cannot prevent the changes to come.

raffishly smokes cigarettes. Christina is a romantic, a beauty on the way to losing both her looks and her free spirit when she eventually succumbs to the drudgery of factory work. Agnes (Brid Brennan) is quiet; still waters run deep, says Michael. Rose (Sophie Thompson) is simple-minded and slow. That would imply that she is mildly retarded, but she doesn't really seem so. Each sister plays her role in maintaining the balance in the Mundy household, with Kate reigning supreme. But even her iron will cannot prevent the changes to come.The sisters eke out a living through Kate's teaching and the glove knitting of Aggie and Maggie, with carefully saved pennies sent to Jack to support his missionary work. Jack's homecoming is a cause for great excitement among the women, and bewilderment for Jack. He is changed, utterly, having abandoning Christianity for the pagan beliefs of the tribes he was meant to convert. He seems mentally ill; he rushes out of the house one evening and starts banging on a bucket with two sticks for no apparent reason. Kate seems to take on the burden of caring for yet another hapless family member with something resembling smug resignation.

Kate's "charges" are troublesome. Rose insists that Danny Bradley (Lorcan Cranitch), whose wife has run off and left him bitter and despairing, wants to marry her. Christina runs back into the worthless Gerry's arms the minute he returns to their village. Even Aggie proposes that the sisters go to the harvest dance using money she has saved. Kate, though tempted, lowers the boom on that idea as being a waste of needed money and foolish for spinsters such as they. Surprisingly, none of the sisters challenges her decision. There seems to be a rhythm in this household of hopes being raised and excitement being built only to be cut down before real happiness can arrive.

Several crises hit the Mundys. Rose runs off to meet Danny, but finds him menacing when she wants to leave him to go home. An all-night search for her ends when Jack finds her with Danny at a pagan ritual in the back hills, where revelers are celebrating the harvest in tribute to the goddess Lughnasa by dancing, drinking heavily, and jumping over a blazing fire. The relief of Rose's return is short-lived. Kate receives a letter dismissing her from her teaching post, and Aggie and Maggie find that their cottage business will be wiped out when a woollen goods factory opens its doors in their village. Perhaps in a final moment of "abandon all hope ye who enter here," the sisters dance furiously to some traditional Irish music issuing from the radio. In a postscript, narrator Michael informs us that Agnes and Rose left home together and lived out their days miserably in London, Christina worked bitterly at the woollen goods factory, Jack "hung on as long as he could," and Kate and Maggie, well, I can't seem to remember what happened to them, but I'm sure it wasn't good. In other words, the story had a typical Irish ending.

This film is episodic and does not build much momentum. The male characters are little more than sketches. The women are the heart of the film, of course, but they don't really seem like a family and their interactions are strangely lifeless. The problem with the script is that symbolism took over from character. We can look at each person as a facet in the emerald that is Ireland: the romanticism of Christina, the ribaldry of Maggie, the stern authoritarianism of Kate, the repressed and released paganism of Jack, the careless, manipulative British presence represented by Gerry. The story is about Ireland itself, but the film plays more like an Irish literature class than a drama. The actors are fine, the setting is evocative, but the humanity is dead. We are treated to ghosts, which may seem on paper to be a good way to tell a memory story, but it doesn't work in practice.

There is also a disconnect between the device of flashing back and including scenes that Michael could not have witnessed and probably was not told about. Indeed, young Michael doesn't make many appearances in the film. His memories should have put him at the center of far more scenes than he is.

Nonetheless, I found the film, if not terribly involving, at least intriguing. Ireland does seem to have a strange hold on its people and a fascination for people of other ethnicities. The characters in Dancing at Lughnasa are moved by the country's invisible hands, fated to be miserable because they are not free. While this film is a lesser work in the chronicles of Ireland's sad history, it still manages to create some sense of engagement while it makes its point. l

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home