Carmen (1983)

Carmen (1983)Director: Carlos Saura

French author Prosper Mérimée’s 1845 novella about the free-spirited Spanish Romy (Gypsy) Carmen has inspired more than 50 film adaptations and, famously, one stupendous opera by Georges Bizet that itself has been filmed several times. In this installment of his filmic odyssey through the world of Latin dance (including Blood Wedding and Love the Magician, which form a trilogy with Carmen; Tango; and Flamenco), Spanish director Carlos Saura has collaborated with celebrated dancer Antonio Gades to reinterpret this tragedy in Spanish terms, in a sense, “returning” Carmen to her country from the fictional Spain of Mérimée’s imagination. It is Saura’s genius to effect this transformation by having the lives of his characters imitate the art of Mérimée and Bizet, thus wholly internalizing the legend of Carmen and giving it new, Spanish, life. (The fact that this transformation occurs in a fictional film further complicates the history of Carmen, making this film more a borrowing of intellectual property than a repatriation of a cultural artifact.) Whatever its geopolitical implications may be, as a film, Carmen plays like a palindrome, as Gades, who plays himself, choreographs a flamenco “Carmen” with an unknown dancer named Carmen (Laura del Sol) assuming the title role.

The film opens with Gades auditioning female dancers. His consummately talented assistant Cristina Hoyos, playing herself, leads the hopefuls through some combinations. Gades singles two or three out to perform alone. Commiserating with famed guitarist Paco de

Lucía (who composed all the dance music for the film) after the audition, he says, “Some of them are good. But none of them are Carmen.” Then the opening credits roll to the strains of Bizet’s opera.

Lucía (who composed all the dance music for the film) after the audition, he says, “Some of them are good. But none of them are Carmen.” Then the opening credits roll to the strains of Bizet’s opera.We move on to a huge dance studio, where dancers are lounging, talking, and trying out steps on each other. The camera pans across de Lucía and other musicians, who are jamming, and settles on Gades, who takes a reel of tape from a messenger, threads it into his tape recorder, and listens. "Pres des remparts de Seville," Bizet’s waltz to be sung by Carmen, flutters on the air and then grows louder and louder as Saura zooms in on Gades’ face, watching him absorb the musical strains and try to visualize them in dance. This device of amplifying Bizet’s score will be used again to telegraph Gades’ state of mind and creative process.

The musicians begin to riff on the aria and come up with a boleras treatment. De Lucía plays it for Antonio, easily convincing him that this version is better suited for dance. Inspired by the new Spanish rendition of the French approximation of Spanish music, Antonio is immediately inspired to begin choreographing his “Carmen.”

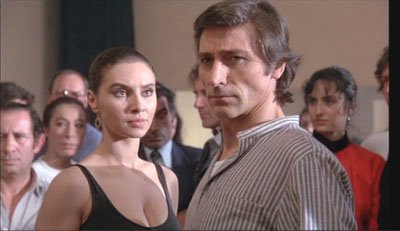

Gades' biggest problem is trying to find his Carmen. He goes to a dance school to look at some of the students. He sits in, watching the raw dancers work their castanets and growing restless until one student, Carmen, runs in late to class. He later visits her at the nightclub where she dances for tourists and asks her to audition at his studio. During the audition, Gades guides her through a pas de deux he has choreographed for Carmen’s seduction of Don José. A series of spins brings them close, face to face. Carmen gazes at him with a sweet insolence; he returns a gaze of helpless lust and fascination. Needless to say, she gets the job.

Cristina is disappointed that she did not get the role as she works with the amateurish Carmen, blasting her off the dance floor with her skill. Antonio tries to calm her but further injures her by saying he needs someone younger to play Carmen. Slowly, Carmen finds herself in the role and in her own skills. When we see del Sol show what she actually can do, it's stunning!

The stage is set for the first dance, in the Seville cigarette factory where the fictional Carmen works. A brilliant score that makes full use of the almost animalistic chanting of the flamenco singers works to bring this confrontational dance of insult and murder to its fever pitch, when

Carmen picks a knife off a table and slashes at the throat of her coworker, played by Cristina. This and all the dances are the best I’ve ever seen committed to film, disproving Fred Astaire’s theory that dance must be shot full body. In the hands of a master director and cinematographer, tight angles, stark lighting, and circular motion communicate perfectly the enmity of the two women—but which women? The dancers or the characters they are playing?

Carmen picks a knife off a table and slashes at the throat of her coworker, played by Cristina. This and all the dances are the best I’ve ever seen committed to film, disproving Fred Astaire’s theory that dance must be shot full body. In the hands of a master director and cinematographer, tight angles, stark lighting, and circular motion communicate perfectly the enmity of the two women—but which women? The dancers or the characters they are playing?The blurring of fiction and reality starts with this astonishing dance and continues to play out as Antonio becomes embroiled in an affair with the untrustworthy Carmen in a scenario that parallels Mérimée’s tale. Dances appear that have little to do with the story and everything to do with Gades' jealousy at being confronted by the reality

of Carmen's marriage, which she swears she intends to end. A card game involving some of the dancers, Gades, and Carmen's husband devolves into a shouting match and then a furious dance duel between Gades and Carmen's husband--that is, a dancer made up to look exactly like her husband. Saura and Gades, who wrote the script of the film together, delight in putting viewers in among the funhouse mirrors and challenging them to distinguish the real from the reflection.

of Carmen's marriage, which she swears she intends to end. A card game involving some of the dancers, Gades, and Carmen's husband devolves into a shouting match and then a furious dance duel between Gades and Carmen's husband--that is, a dancer made up to look exactly like her husband. Saura and Gades, who wrote the script of the film together, delight in putting viewers in among the funhouse mirrors and challenging them to distinguish the real from the reflection.In the end, Antonio follows Carmen off the dance floor, which she has left in disgust as he, as Don José, has been challenge-dancing the bullfighter for whom the character of Carmen has rejected him. She repulses him, appearing to be speaking to him as Antonio, not Don José. She disappears into a doorway, and we see only Gades pleading and arguing into this hidden space. Gades removes a switchblade from his back pocket and stabs into the space. Carmen crumbles back into the frame. The camera pans back across the dance studio, where the rest of the cast is milling about, indifferent to what has happened in the corner of the room. Was this a “real” event or an invention of Gades the choreographer? In fact, it is neither. It is Saura completing his version of Carmen with a question mark. l

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home