The Ipcress File (1965)

Director: Sidney J. Furie

The Cold War that pitted Western Europe and the United States against the Soviet bloc countries in Eastern Europe proved fertile to the imaginations of writers, filmmakers, and fans of both. As a child in 1960s America, I remember enjoying the black and white, cone-nosed spooks in Mad Magazine's "Spy vs. Spy" cartoon, Don Adams as bumbling spy Maxwell Smart in the TV series "Get Smart," British TV imports like "The Prisoner" and "Secret Agent" ("they're giving you a number and taking 'way your name"), and of course, the ultracool 007 in the exciting James Bond movie franchise based on Ian Fleming's popular book series. Taken together, I suppose my impressions of spies were that they either were silly and confused or cool supermen whom fate could toss but never tumble. Neither vision was based in reality, but I wasn't sufficiently interested at the time to learn more.

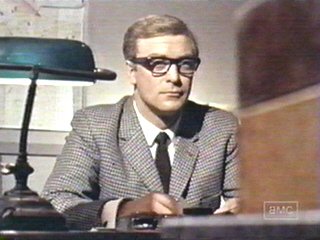

It is only at this late date that I realize there were alternative views of spies, ones closer to the truth, available in the 60s. One prime example that showed audiences where spies came from and a bit more of what they actually did was The Ipcress File. Based on a novel by Len Deighton, The Ipcress File shows British spies largely without the upper-class pedigrees and casual success assumed by the James Bond flicks. Instead, these spooks are former military men--"passed over majors" as one of the characters says to another--probably with less-than-stellar academic careers at second-rate private schools. The main character, a lowly operative named Harry Palmer (Michael Caine), is a working-class bloke who, when given the choice between jail and espionage, chose the latter. He is described as follows: "Insubordinate! Insolent! A trickster. Perhaps with criminal tendencies."

Palmer hardly cuts a dashing figure, with his double-thick glasses and menial work in surveillance. When we first meet him, he's oversleeping--alone--as a wind-up alarm clock rattles on for a godawful long time. Reporting late to his surveillance assignment, he is redirected to his boss, Colonel Ross (Guy Doleman), and reassigned to the counterespionage unit of Major Dalby (Nigel Green) to replace an agent who was killed during the kidnapping of a scientist he was guarding. Orders are to retrieve the scientist, one of more than 100 lost to government service through retirement, a better offer in the private sector, or a rather mysterious inability to work. We're not talking a commando rescue into a heavily armed compound in the middle of the ocean here. The British government plans to buy him back from the kidnappers, plain and simple. Toward that end, the agents under Dalby are sent out to find the mastermind of the kidnapping, a fellow named Brantby (code name "Bluejay"), played with effete relish by Frank Gatliff. Palmer easily locates him with the help of a friend in Scotland Yard, but Brantby refuses to be pinned down.

A rescue attempt is made based on a hunch Palmer has about where the scientist is being held. No trace of the man is found, but a length of audiotape stamped with the word "Ipcress" is found in a still-warm stove. Conventional negotiations somehow are arranged by Dalby, the scientist is paid for and returned, but he is later found to have been rendered entirely useless to the government. A colleague of Palmer's (Gordon Jackson) suspects stress-induced brainwashing and shares his evidence with Palmer, putting both their lives at risk.

The Ipcress File is a fairly predictable story of dirty tricks in the spy business, at least to those of us who have been watching these kinds of movies for years. What made it remarkable at the time and what still makes it remarkable is what a crucible of its time it was. We are watching Britain in transition, as the regal view the nation always had of itself started to give way to a more realistic approach to life on the island. As Rod Heath pointed out in his essay on this blog "Look Back: Influences and Major Figures of the British Free Cinema," this was a film of the "generation that had been drafted into the Second World War, gained status and experience in their temporary socialisation of British society as well as a college education, but found themselves deeply frustrated, as the whole country did, in the post-War malaise."

Palmer appears to be a gourmet cook and patron of the fine arts, presaging today's yuppies with his bending (but not breaking) of the rules and his taste for the finer things without the entitlement of birth and breeding to them. Spying consists of filling out paperwork, playing politics with other policing agencies in and outside of one's own government, and being told what a lousy job one is doing. Palmer's not indignant that the scientist has been brainwashed--he doesn't really care about the intellectual loss to his country--he's upset that Brantby got good money for damaged goods. In the end, when Palmer complains to Ross that he might have been killed or driven mad by Ross's manipulation of him to find a mole in the organization, he gets his comeuppance when Ross counters, "That's what you're paid to do." So much for spying as a lifestyle. It's just a job, and not a very good one at that. At least Palmer gets to be a successful womanizer.

Palmer appears to be a gourmet cook and patron of the fine arts, presaging today's yuppies with his bending (but not breaking) of the rules and his taste for the finer things without the entitlement of birth and breeding to them. Spying consists of filling out paperwork, playing politics with other policing agencies in and outside of one's own government, and being told what a lousy job one is doing. Palmer's not indignant that the scientist has been brainwashed--he doesn't really care about the intellectual loss to his country--he's upset that Brantby got good money for damaged goods. In the end, when Palmer complains to Ross that he might have been killed or driven mad by Ross's manipulation of him to find a mole in the organization, he gets his comeuppance when Ross counters, "That's what you're paid to do." So much for spying as a lifestyle. It's just a job, and not a very good one at that. At least Palmer gets to be a successful womanizer.The Ipcress File is filled with sharp dialogue, interesting performances and character actors, and an excess of trick camera angles so popular with the practi

tioners of the Free Cinem

tioners of the Free Cinem a movement. The low, skewed camera angles that predominate make it seem as though the cinematographer was Toulouse-Lautrec. There is also a great fondness for frames of all sorts. Oftentimes, characters are trapped inside doorways and window frames. You can also find them behind cages and bars of various types. My favorite was a bird's-eye shot through the top of a lampshade onto the face of a dead man on the floor. The look is amusing but amateurish. These camera angles do not seem justified by the material, particularly as presented. Where noir uses such devices to distort reality, a film that deals in kitchen-sink realism should strive for a more verite feel. Still, I can forgive the enthusiasm that went into these set-ups, and kind of wish I'd been in on the planning. I enjoyed The Ipcress File a lot. l

a movement. The low, skewed camera angles that predominate make it seem as though the cinematographer was Toulouse-Lautrec. There is also a great fondness for frames of all sorts. Oftentimes, characters are trapped inside doorways and window frames. You can also find them behind cages and bars of various types. My favorite was a bird's-eye shot through the top of a lampshade onto the face of a dead man on the floor. The look is amusing but amateurish. These camera angles do not seem justified by the material, particularly as presented. Where noir uses such devices to distort reality, a film that deals in kitchen-sink realism should strive for a more verite feel. Still, I can forgive the enthusiasm that went into these set-ups, and kind of wish I'd been in on the planning. I enjoyed The Ipcress File a lot. l

3 Comments:

At 7:34 PM, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

I'm a big fan of The Ipcress File and also its sequel, Funeral In Berlin, which, although it isn't directed with as much style as Ipcress, is even more dryly witty. I'll politely disagree on the style issue. Furie wasn't after kitchen sink realism per se - the realistic quotient is important, but the skewed angles, the craning glimpses, the events witnessed through mirrors and bizarre angles, the occasionally cubist visual sense - is about giving things a sense of paranoia, breaking up standard points of visual reference to make the world seem jagged and untrustworthy. Furie isn't always consistent in expressing this - he as no artist but an extremely accomplished stylist and I think you argue some modern stylists for hire like Tony Scott follow his lead, in that they create visual textures which are dense but not deep - and som his touches, like the one you mention of the shot through the lampshade on the corpse, are just flashy, but I still adore the film's cool artistry. In the end, the film-makers did want a blockbuster, so Furie's approach, combining realism and technocratic gloss, was perfect. Compare it to Martin Ritt's style for The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, a film which is supposed to be pungent in its anti-romantic realism and Ritt's style very much is.

At 7:50 PM, Marilyn said…

Marilyn said…

I understand and agree that he was trying to create a sense of paranoia. But he went overboard. I would say a good 70% of the shots were low angle, a peculiar choice even if used effectively. His hemmed-in views (I particularly like how he squares Caine's face with those enormous glasses and otherwise uses eyeglasses almost like camoflage, for example, on the agent tailing Palmer) are much more successful. I think one could assume a certain paranoia about spying--it's almost the "you understood" of the profession. His real achievement is to break the audience out of that fantasy world and show that spies are real and they have the same drudgeries in their lives as we do. It's a lot easier to feel fear when you can identify with the person in danger.

At 9:00 PM, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

Check out Michael Caine's biography What's It All About for a lot of good detail on how he and the film-makers conceived Harry Palmer (he didn't even have a name in the novel, which was first-person).

Post a Comment

<< Home