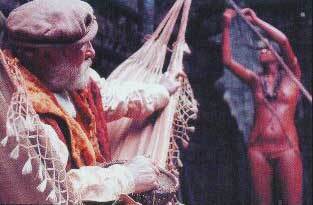

How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francês, 1971)

How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francês, 1971)Director: Nelson Pereira dos Santos

During the 1960s and early 1970s, Brazil was a country enslaved to a military dictatorship--and, miraculously, in the middle of a cinematic renaissance. Brazilian filmmakers, inspired by Italian neorealism and the French New Wave, declared they would create a new type of cinema for their country--Cinema Novo (Noh voo). Films of this movement tackled social issues and promoted "tropicalism," that is, a peculiarly Brazilian sensibility rather than an imitation of European aesthetics that was more usual among Brazilian films. Criticism of the military regime, which had been fairly open in the beginning years of Cinema Novo, increasingly had to become allegorical, often hearkenly back to traditional Brazilian literature in order to camoflage the filmmakers' disdain.

Nelson Pereira dos Santos made a masterpiece in 1963 called Barren Lives (Vidas Secas), a straight-on view of the cruel lives of a poor Brazilian family in the country's arid, barren Northeast. By 1971, when How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman premiered, Pereira dos Santos had been forced to retreat into allegory, substituting the incursions of the Portuguese and French into Brazil for the harshness of the current dictators. Although Frenchman is missing the simple beauty and emotional core of Barren Lives, the film achieves something quite remarkable--a straight-on view of Brazilian tribal society as it clashed with the duplicitous Europeans out to rape it of its natural resources.

The film takes place in 1594. The Tupinambas Indians have allied themselves with the French. Their enemies, the Tupiniquins, are on the side of the Portuguese. We see French and Portuguese fighting each other in crude skirmishes, and fighting amongst themselves as the leaders wish to maintain order and European civility while certain of their number prefer to take advantage of a native society unburdened by sexual repression. A Frenchman (Arduino Colassanti) is found to be "mutinously" fornicating with native girls, and he is captured and executed by being pushed off a cliff into the ocean while bound in chains. A letter written by the head of the expedition claims he was unchained and chose to jump to his death, our first look at the duplicity that surrounds the conquest of Brazil.

Miraculously, he survives the fall, only to be captured by some Portuguese and Tupiniquins. When the Tupinambas raid the camp in which he is being held, they seize him and bring him back to a vengeful chief Cunhambebe (Eduardo Imbassahy Filho), who is convinced he is Portuguese and decides to enslave him and kill and eat him after 8 moons (8 months) have passed to avenge the deaths of many Tupinambas at the hands of the Portuguese.

A French merchant (Manfredo Colassanti, Arduino's father) comes to the village, and the French captive pleads with him to convince Cunhambebe that he is not Portuguese. The merchant says emphatically that he is Portuguese for reasons still obscure to me. He advises the captive to sit back and enjoy himself. He will be an honored guest for the next 8 months, will have Seboipepe (Ana Maria Magalhaes), a woman presented to him on the first night of his capture, as a wife, and probably will escape. Slowly, the captive establishes a routine and quickly goes native, shedding his clothes, shaving the top of his head, and eventually fighting alongside the Tupinambas to defeat the Tupiniquins.

He believes he can win his life back by being loyal and helpful to Cunhambebe. He secures 10 kegs of gunpowder from the merchant in exchange for some buried gold and jewels. Unfortunately, both men become greedy and fight over the treasure. If the captive believes he can secure his freedom by presenting the chief with gunpowder, why is it necessary for him to have treasure? This is one of the ways this film shows how truly illogical and irrationally acquisitive the Europeans are.

But the native Brazilians aren't let off the hook. Cunhambebe declares that he will never forgive anyone who has wronged him and his people. An instinct for violence thus seems to perpetuate itself in the Brazilian bloodline, which is one of the observances of the film's intertitles that give the views of Europeans from that time. This depiction of bloodlust is, perhaps, a veiled critique of the modern Brazilian dictatorship that put its own values above the good of the Brazilian people.

Given the title of this film, I don't think it's giving too much away to say that the captive is indeed killed and eaten. We think, like he does, that reason will out. But the native Brazilians have as much use for reason as they do for clothing. We are given a preview of the ceremony as he and Seboipepe enact it as a prelude to making love. Of course, the Frenchman tries to run, but Seboipepe shoots him with an arrow and fills their canoe with leeches to prevent his escape. In his final moment, he yells that his killers will be destroyed by his people, an oath he has been told to say by Seboipepe, and one that comes to pass. Pereira dos Santos thus takes a final swipe at the dictators of Brazil, heirs of the European conquerers who were continuing to destroy the essence of Brazilian life.

If you're not familiar with Cinema Novo films, this engrossing film would be a good place to start. It's sure to give you an appetite for more. l

2 Comments:

At 3:45 PM, Lady Wakasa said…

Lady Wakasa said…

Marilyn - thanks for the info on Cinema Novo! I saw Macunaima, which sounds like it has the same flavor as Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francês, in 2004, but didn't have much background on it. I'll have to track this down.

At 6:29 PM, Marilyn said…

Marilyn said…

You're welcome. Info courtesy of my Brazilian cinema class. My instructor, Gabe Klinger, has an article about Cinema Novo director Glauber Rocha on Senses of Cinema's Great Directors site.

Macunaima, which I saw in the class, is based on a classic Brazilian novel, and has a gleeful abandon that is quite different from Como Era Gostoso. Despite what the box says, this film is not a black comedy. It is a somewhat ridiculous circumstance, but there is nothing funny about the movie. It's really quite powerful.

Post a Comment

<< Home