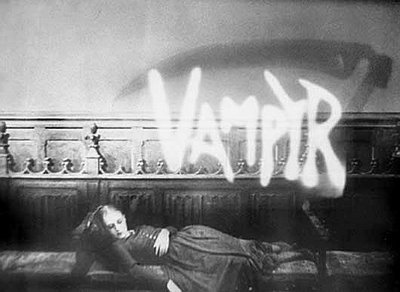

Vampyr: Der Traum des Allan Grey (1931)

Vampyr: Der Traum des Allan Grey (1931)Director: Carl Theodor Dreyer

By Roderick Heath

1931 was a watershed year for horror cinema. With Tod Browning’s crepuscular, but patchy Dracula, James Whale’s Gothic fairy tale Frankenstein, Rouben Mamoulian’s vivid Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Michael Curtiz’s flashy, absurd Doctor X, the genre found its feet in the Hollywood of sound, and made a big impact at the box office. At the time, they set the pace, created stars, and codified the film concept of Mary Shelley’s homunculus, Bram Stoker’s vampire, and Robert Louis Stevenson’s doppelganger (Doctor X purloined the mad scientist imagery of pulp magazine covers for the cinema). Yet despite their iconic status, the Universal-brand horror films have little relevance to the modern genre. Many of today’s films, however, owe something to another 1931 film.

Vampyr, supposedly inspired by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Carmilla” and other stories in Le Fanu’s In a Glass Darkly collection (in truth it owes little but mood to Le Fanu), was at the time completely overshadowed. It was directed and written by Carl Theodor Dreyer, the Danish director who had begun with the hit Master of the House (1924). But as Dreyer became more formally rigorous and experimental, exemplified by his now-famous La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1927), he lost audiences. German and Scandinavian directors had a field day with macabre subjects, for visual rhapsodies and post-WWI expressions of mental anguish and collapse. These included Victor Sjöstrom (The Phantom Carriage, 1920), Benjamin Christensen (Häxan, 1921), F. W. Murnau (Nosferatu, of course, 1921), Abel Gance (Au Secours!, 1923), Paul Leni (Waxworks, 1924), and Fritz Lang (coauthor of Das Cabinet Des Dr Caligari, 1919, and director of Der Meude Tod,1921).

Dreyer’s efforts with Vampyr were not about telling a story through the symbolic prisms of Expressionism, but pursuing the tantalizing challenge of Surrealism, to capture the essence of a dream as itself; to replicate the sensations, the elided realities and meanings, the disjunctive perspectives. The film’s dialogue is in English, German, and French, with an eye to making export easier, but also contributing to its “nowhere” mood.

Vampyr was produced privately by the film’s star, Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg (acting under the name Julian West). The sallow-faced Gunzburg plays wandering geek and professional busybody Allan Grey, loosely based on one of Le Fanu’s recurring heroes, (he’s called David Gray in the English version) who tramps about the countryside in tweed suit, jaunty hat, with a net on his shoulder. He suggests a holidaying entomologist with a morphine habit and an uncoventional sex life. He arrives in Courtempierre, an isolate d Franco-German village, passing, at the ferry bell, a black figure carrying a scythe, a sight that would make most men turn and head in another direction. The opening scrawl tells us that Allan has had many strange encounters; he’s a kind of proto-Fox Mulder. He settles into a small hotel room, the walls of which are covered in macabre, medieval decorations. He hears someone muttering outside, and catches a brief glimpse of a gnarled-faced man haunting the upstairs. He is awoken at midnight by a visitor; not, as he may have been hoping, the innkeeper’s daughter, but aged local chatelaine (Maurice Schutz) who makes wordless entreaty to him, as an outsider and therefore apparently trustworthy, to care for a package, marked “Not To Be Opened Until My Death.”

d Franco-German village, passing, at the ferry bell, a black figure carrying a scythe, a sight that would make most men turn and head in another direction. The opening scrawl tells us that Allan has had many strange encounters; he’s a kind of proto-Fox Mulder. He settles into a small hotel room, the walls of which are covered in macabre, medieval decorations. He hears someone muttering outside, and catches a brief glimpse of a gnarled-faced man haunting the upstairs. He is awoken at midnight by a visitor; not, as he may have been hoping, the innkeeper’s daughter, but aged local chatelaine (Maurice Schutz) who makes wordless entreaty to him, as an outsider and therefore apparently trustworthy, to care for a package, marked “Not To Be Opened Until My Death.”

Allan, knowing such packages never bode well, tries to follow the old man. He wanders the day-for-midnight wonderland of the village, where shadows without forms move by themselves and dogs and children moan constantly. Allan explores a ruined chateau, which, with its cavernous rooms and labyrinthine halls, exactly conjures those shifting space-time traps of dreams. It is vaguely inhabited by a soldier and a one-legged man, both of whom, when they sleep, have their shadows walk off and perform nefarious deeds at someone else’s bidding. There’s also an ancient crone (Henriette Gérard) wearing Flemish dress of the 1600s and a bespectacled, meek-looking but creepy doctor (Jan Hieronimko - what a name!). In the film’s most bizarre and wondrous moment, the camera explores a vast attic where a populace of shadows are dancing to snatches of Gypsy fiddle, until the crone, on a lower floor, framed by dangling, rotating cartwheels, angrily lifts her cane for silence, which she gains instantaneously. She hands the doctor a vial of poison. Clearly, they’re in league for some awful purpose.

Allan escapes the ruin and reaches the chatelaine’s house just in time to see the shadows of the soldier and one-legged man shoot the chatelaine. His assassination seems almost expected by the household, for he’s been fighting this oppressive, intangible evil. Allan is invited to stay and protect them, Gisele (Rena Mandel, an ex-nude model), the chatelaine’s  daughter, Her sister Leone (Sybille Schmitz, the film’s only professional actor) is continually lured into the garden and drained of blood by the crone. In one of the most needle-sharp erotic-horror moments in cinema, Leone awakens from a delirium and latches eyes on her sister, her happy smile broadening into a grin of perverse lust, scaring Gisele away. A servant is sent by carriage to fetch the police; when it comes rolling back, the driver is bloody and lifeless. Allan, exhausted, falls asleep. He dreams Gisele has been kidnapped and tied up in the ruin, and then finds his own body in a coffin; in a bravura long POV shot, we are Allan as the lid of his coffin is nailed on and he is carried by the gloating faces of the doctor and the crone.

daughter, Her sister Leone (Sybille Schmitz, the film’s only professional actor) is continually lured into the garden and drained of blood by the crone. In one of the most needle-sharp erotic-horror moments in cinema, Leone awakens from a delirium and latches eyes on her sister, her happy smile broadening into a grin of perverse lust, scaring Gisele away. A servant is sent by carriage to fetch the police; when it comes rolling back, the driver is bloody and lifeless. Allan, exhausted, falls asleep. He dreams Gisele has been kidnapped and tied up in the ruin, and then finds his own body in a coffin; in a bravura long POV shot, we are Allan as the lid of his coffin is nailed on and he is carried by the gloating faces of the doctor and the crone.

Allan awakens with a jolt as panic erupts in the house. The doctor, having called to check on Leone, has poisoned her. Allan and the chatelaine’s loyal servant (Albert Bras) open the package entrusted to Allan by the chatelaine. It’s a book on vampires from the 1770s, based on papers found in Faust’s collection. Despite this lip-smacking suggestion of forbidden lore, it only relates basic stake-in-the-heart stuff, and gives a clue to the vampire’s identity by detailing how, in the 1750s, an outbreak of vampire attacks in Courtempierre were blamed on a dead woman named Marguerite Chopin. Allan and the servant search the graveyard for Chopin’s grave and find it contains the crone. The servant stakes the vampire as Allan searches for Gisele in the ruin. He unties her, scares off the doctor, and gets her out of the haunted village by boat. The servant gets final revenge when he finds the doctor has cornered himself in a flour mill; he sets the machinery rolling and the perfidious medico slowly drowns in tons of white flour, shouting “I don’t want to die!” Might have thought of that before you started poisoning girls and mistreating dogs!

In developing this cryptic, often blackly comic film, Dreyer and cinematographer Rudolph Mate were inspired a flour mill wreathed in dusty clouds they passed while on a train, a sight that inspired the finale and the hazy, washed-out visuals produced by false light shone on the lens. Contributing was Nosferatu’s designer Hermann  Warm, and like that film, Vampyr shares an appealing rejection of studio-created atmosphere for careful manipulation of real settings. Vampyr is technically primitive, with poor sound from an experimental system. Dreyer used this flaw to good effect, muting the dialogue and reduces the soundtrack to menacing rumbles and barely heard sonorous music, adding to the ruined look. Dreyer seems to have been the first director to seek an illusion of the uncanny by devolving the techniques of film, something now every film student tries at least once. Yet Dreyer’s camera is sublimely mobile, roaming halls and rooms with restless, hungry fascination.

Warm, and like that film, Vampyr shares an appealing rejection of studio-created atmosphere for careful manipulation of real settings. Vampyr is technically primitive, with poor sound from an experimental system. Dreyer used this flaw to good effect, muting the dialogue and reduces the soundtrack to menacing rumbles and barely heard sonorous music, adding to the ruined look. Dreyer seems to have been the first director to seek an illusion of the uncanny by devolving the techniques of film, something now every film student tries at least once. Yet Dreyer’s camera is sublimely mobile, roaming halls and rooms with restless, hungry fascination.

Vampyr pilots the next few generations’ worth of experimental film in its attempts to capture the uncanny. In The Ring, when one character judges the mysterious videotape as good in a student film fashion, he’s absolutely right, but that tradition of experimental short, and, more recently, death metal music videos trying to recreate the ugly dissociations of nightmares, have some roots in Dreyer’s style. It’s hard to imagine David Lynch’s films, especially Eraserhead, without Dreyer. Much of what Lynch accomplished - weird soundtrack, disorientating editing, sickly half-seen visions - is present here. But Vampyr is gossamer in its invocation of the morbid, more in the key of Mahler than evanescence. Vampyr is modernist, in its war with perspective, reality, and the limitations of the senses, and feels particularly reminiscent of Kafka - especially in its dark humor, the way Allan keeps walking into the weirdest circumstances without blanching and falls in love with Gisele at the drop of a hat. It’s also a pure invocation of the spirit of the Gothic genre, that European sense of being enveloped and suffocated by history, something that ultimately was lost on Hollywood. Vampyr envisions a world haunted by loss and a past only visible in shreds, entrapped by identity but adrift between realities. Although Allan and Gisele escape from the fog-shrouded bank, they arrive on the side that our scythe-wielding friend crossed to earlier; it’s hard to tell if the waking world will be better. That waking world was about to collapse in on itself. Under the Nazis, German horror cinema would be extinguished, thanks to their detestation of the psychological and the genre’s too-pointed realisation of what forces were stirring under the surface - Das Cabinet des Dr Caligari envisioned the country as a giant insane asylum waiting for an authoritative administrator.

Vampyr is modernist, in its war with perspective, reality, and the limitations of the senses, and feels particularly reminiscent of Kafka - especially in its dark humor, the way Allan keeps walking into the weirdest circumstances without blanching and falls in love with Gisele at the drop of a hat. It’s also a pure invocation of the spirit of the Gothic genre, that European sense of being enveloped and suffocated by history, something that ultimately was lost on Hollywood. Vampyr envisions a world haunted by loss and a past only visible in shreds, entrapped by identity but adrift between realities. Although Allan and Gisele escape from the fog-shrouded bank, they arrive on the side that our scythe-wielding friend crossed to earlier; it’s hard to tell if the waking world will be better. That waking world was about to collapse in on itself. Under the Nazis, German horror cinema would be extinguished, thanks to their detestation of the psychological and the genre’s too-pointed realisation of what forces were stirring under the surface - Das Cabinet des Dr Caligari envisioned the country as a giant insane asylum waiting for an authoritative administrator.

Vampyr was ignored on release. Dreyer did not make another film for 13 years, until with Day of Wrath (1943) he returned to studying the legacies of historical evil and psychological oppression. Sybille Schmitz later starred in Frank Wisbar’s version of the death-and-the-maiden theme, Faehrmann Maria (1936), which Wisbar remade when he decamped stateside as PRC’s Strangler in the Swamp (1946). Nicholas de Gunzburg became an investment banker in New York, a notable sight for many years walking the streets displaying the same haunted, soulful expression he sports in Vampyr. l

You can now read Rod Heath's poetry and other writing on Rod Writes, http://rodwrites.blogspot.com.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home