Chicago (2002)

Director: Rob Marshall

Grand, isn't it? Great, isn't it? Swell, isn't it? Fun, isn't it?

When Fred Ebb wrote those lyrics for John Kander’s catchy celebration of the immorality of the Jazz Age, “Nowadays,” for the stage musical Chicago, he likely was making an ironic statement about America in the 1970s. I don’t know if his lyrics for that song, “You can even marry Harry/But mess around with Ike,” had anything to do with the landslide victory Richard Nixon, Dwight (Ike) Eisenhower's Vice President, received in the year the play premiered (1972), but I do know that Kander and Ebb sounded an early warning of the cynicism and lawlessness to come. Their message fell on deaf ears, and their musical was a flop.

In the 1990s, Chicago returned in triumph to stages all over the world, and the film won the Best Picture Oscar for 2002. I wonder sometimes what the success of Chicago today says about us. In 1972, we still thought of ourselves as liberal, warring on poverty, and peacing on war. By the 1990s, bloody war on others was still the rage, and bloodless war on the poor was well underway. Everyone could understand and many aspired to be like Chicago's greedy, amoral lawyer Billy Flynn. We also had just experienced a media frenzy over a celebrity murder case that would have pushed Velma Kelly’s and Roxie Hart’s headlines out of the paper altogether. This clearly was a musical for our times.

The show opens in a backstage frenzy of nightclub performers getting ready for their acts. One such performer rushes to her dressing room amid questions about where the other half of her sister act is. Velma (Catherine Zeta-Jones) answers flatly, "She's not herself," and deposits her things, including a gun, in her vanity. She rushes on stage to perform her act alone, amid the writhing chorus boys and girls that Chicago's choreographer Bob Fosse is known for. At a climactic moment in the dance, Velma transforms into a glamorous blonde. It is Roxie (Rene Zellweger), an aspiring singer and dancer imagining her heart's desire. Reality intrudes on them both, as furniture salesman Fred Casely (Dominic West) hustles Roxie back to her apartment for the horizontal tango, and the cops come to take Velma away for murdering her two-timing husband and sister.

This opening sets up the structure of the film beautifully. It uses quick cuts to shorthand the story to us and pulse the film with energy, as well as establish a relationship between Velma and Roxie that will fill the frames of this story. The use of music and dance to telegraph fantasies and underlying motivations also is established, undercutting one of the main objections people have to musicals--they can't believe a story in which people leave the plot to break into song and dance. In Chicago, we don't have to take these intrusions literally and, therefore, can enjoy the interludes (which, in fact, comprise almost the entire film) without worrying about the logic of them.

A month passes in the wink of an eye. Casely has decided to end things with Roxie and does so in particularly rough fashion. This does not seem to bother  Roxie as much as the fact that Casely lied to her about being able to get her into show business. She does what any self-respecting woman in this film does--she plugs him full of lead. After unsuccessfully trying to pin the murder on her doltish husband Amos (John C. Reilly), she arrives at Cook County Jail to take her place among the other women murderers and learn the ropes of self-preservation through self-promotion.

Roxie as much as the fact that Casely lied to her about being able to get her into show business. She does what any self-respecting woman in this film does--she plugs him full of lead. After unsuccessfully trying to pin the murder on her doltish husband Amos (John C. Reilly), she arrives at Cook County Jail to take her place among the other women murderers and learn the ropes of self-preservation through self-promotion.

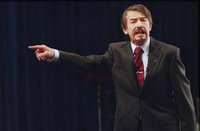

It's a merry ride Chicago takes us on. Roxie deposes Velma as the flavor of the month and shows her cunning in holding the spotlight for the duration of her incarceration. Billy Flynn (Richard Gere) is a master manipulato r, illustrated by the superb "We Both Reached for the Gun" number, in which Roxie is a dummy on ventriloquist Billy's knee, and in the spin-control cross-examination at Roxie's trial, "Tap Dance." The film has a happy ending, if you want to call it that, with our two ladies of larceny making a comeback on the stage of the Chicago Theatre. F. Scott Fitzgerald said there are no second acts in American lives, but our endless fascination with celebrity has proven him wrong.

r, illustrated by the superb "We Both Reached for the Gun" number, in which Roxie is a dummy on ventriloquist Billy's knee, and in the spin-control cross-examination at Roxie's trial, "Tap Dance." The film has a happy ending, if you want to call it that, with our two ladies of larceny making a comeback on the stage of the Chicago Theatre. F. Scott Fitzgerald said there are no second acts in American lives, but our endless fascination with celebrity has proven him wrong.

Rob Marshall’s choice to cast actors with limited or no background in musical productions in the leads was an interesting one. In a story obsessed with celebrity, choosing to cast some of Hollywood's biggest stars adds to the irony of the story. At the same time, I think that the first-class acting chops of these performers, particularly Zellweger, add depth to the portrayals. The stage production used no realistic scenery and was close to being sung through, which heightens the unreality of the proceedings. The convincing performances of the cast ground this film and add to the power and poignancy it offers.

I'm sorry Marshall chose to cut "Class," the duet between Velma and Mamma Morton (Queen Latifah), the prison matron/fixer. The deleted scene is on the DVD and deserved to be in the final cut. Who knows why it wasn't. I also quibble with his decision to cast Christine Baranski as obsequious reporter Mary Sunshine. Baranski is a favorite of mine, but the phoniness of the news coverage would have been better highlighted if he had stuck with the strategy of the stage production and depicted Sunshine as a very masculine-looking drag queen.

Still, Chicago makes few mistakes. It is masterfully crafted and enormously entertaining. And it still manages to throw a pie at the audience and strike them right in the kisser. Grand, isn't it? l

The Pride of the Yankees (1942)

The Pride of the Yankees (1942)

The Brothers Grimm (2005)

The Brothers Grimm (2005)