Footlight Parade (1933)

Footlight Parade (1933)

Director: Lloyd Bacon

Dance Director: Busby Berkeley

In 1933, Warner Bros. Pictures provided audiences with three classic movie musicals with almost identical creative teams. The first was 42nd Street, the second was Gold Diggers of 1933, and the third was Footlight Parade. All three films featured Ruby Keeler and Dick Powell, the reigning ingenue couple of the 30s; all had dance numbers by Busby Berkeley; and all included memorable music by Harry Warren. But Footlight Parade is by far my favorite, and the most accomplished of the three films. Here's why.

Although Warner Bros. was the leader in talking pictures and had the first music synched with the images on screen (1927’s sensation The Jazz Singer), MGM was the gold standard in movie musicals. MGM, specifically producer Arthur Freed, understood the importance of weaving music and dancing into a story, a technique epitomized by such MGM gems of the 1930s as The Merry Widow, Monte Carlo, The Great Ziegfeld, and culminating in the timeless The Wizard of Oz.

Many 1930s Warner Bros. musicals tended to have an odd structure—frontloading the film with a big production number, filling a lengthy middle with a conventional feature film, and ending with a couple more show-stopping production numbers. 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933, and Footlight Parade all fit this format. Part of the reason for this structure had to do with the fact that Busby Berkeley was the director of the musical portions, and there is simply no way a Berkeley production number can have any bearing with reality. They are short films in themselves, and excellent ones at that, particularly in each of these films.

So what’s so different about Footlight Parade? Ruby Keeler’s acting and dancing skills improved measurably from her debut in 42nd Street to her featured, but secondary role in Footlight Parade. Her break-the-floor slapping and tapping took on a little more lightness and precision, and she danced better in combination with other dancers.

While each film has a showbiz theme, Footlight Parade has one that sheds a lot of light on the history of films, and particularly on the adaptation of stage performers to the silver screen. In 42nd Street, we have a standard story about putting on a show in distressed circumstances. Gold Diggers gives us a good idea of the high unemployment during the Depression, particularly among show people, but spends the majority of its time focusing on a flip story of how three showgirls land wealthy husbands. Footlight Parade gives us a context for the production numbers that actually helps make sense of how lavish (though certainly unrealistically so) they are.

The most important difference between the three films, however, is that Footlight Parade stars James Cagney and Joan Blondell. These two wonderful actors--Cagney, a bonafide star, and Blondell, an underrated actress of enormous warmth and appeal--had a history together, beginning on Broadway in the hit play Penny Arcade and continuing to Hollywood, where they reprised their parts in this play in its film version, Sinner’s Holiday (1930). Their chemistry and timing help define and flesh out their characters' relationship in Footlight Parade of career-driven boss Chester Kent and Nan Prescott, dedicated secretary in love with Kent. Their line readings are never clichéd or throwaway. For example, in this exchange:

Chester Kent: Sometimes I get the feeling you don't like anybody.

Nan Prescott: If you only knew.

We catch Nan’s longing look, which Kent misses, and it’s a real heart-tugger.

The film tells the story of a writer of stage musicals (Kent) who can’t get them produced anymore because audiences have been abandoning the legitimate theatre for the movie theatre. Two producers, Al Frazer (Arthur Hohl) and Silas Gould (Guy Kibbee), take Kent to a nearby movie house and show him that live dance productions called prologues, which show between screenings of the film, satisfy an audience’s craving for live theatre. The prologues, however, are costly to produce. Kent gets an inspiration to create a factory-like setting (inspired, no doubt, by the type of movie factory in which Footlight Parade was made) for the production of prologues. Stock routines could be taught to a unit of dancers and singers and then sent on the road. With numerous units able to fill the demand, success should be assured.

Keeler plays super-efficient production assistant Bea Thorn, dressed as all super-efficient women should be in round, horn-rimmed glasses, matronly clothing, and sensible shoes. Dick Powell is Scott Blair, a new protégé of Si Gould’s wife Harriet (Ruth Donnelly) whom Kent is forced to take on. Fortunately, Scotty can sing. He also inspires Bea to sto p being sensible, fall in love, and return to her roots as a hoofer. There are several intrigues, including a romance Kent starts with Vivian (Claire Dodd), a down-and-out gold digger who is staying with Nan; a mole in Kent’s organization who is feeding his ideas to a competitor; and Kent’s mercenary ex-wife (Renee Whitney) returned to claim her share of his good fortune—which he doesn’t have because his partners have been cheating him. The story is told briskly, with sparkling dialogue and equally sparkling stars to speak it. Cagney is having a ball doing what he always loved best—singing and dancing.

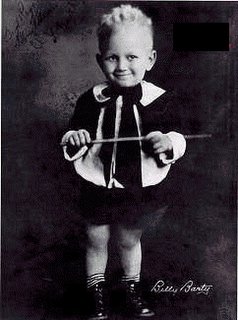

p being sensible, fall in love, and return to her roots as a hoofer. There are several intrigues, including a romance Kent starts with Vivian (Claire Dodd), a down-and-out gold digger who is staying with Nan; a mole in Kent’s organization who is feeding his ideas to a competitor; and Kent’s mercenary ex-wife (Renee Whitney) returned to claim her share of his good fortune—which he doesn’t have because his partners have been cheating him. The story is told briskly, with sparkling dialogue and equally sparkling stars to speak it. Cagney is having a ball doing what he always loved best—singing and dancing.  And speaking of singing and dancing, feast your eyes on the production numbers. “Honeymoon Hotel” has Keeler and Powell getting married and spending their first night together in a hotel filled with honeymooners. In true precode fashion, the sex is more than alluded to, the women are scantily clad, and Billy Barty, the most successful midget in movies, plays a not-so-innocent child who follows the chorus girls around the corridors. “On a Waterfall” has to be seen to be believed. From a simple stage duet by Keeler and Powell, an entire soundstage full of water slides and an enormous pool emerge. Berkeley’s famous overhead camera shots show the mermaids move into the kaleidoscopic formations for which he was known. The cameras take us underwater, too, for some sexy shots. Clearly, these

And speaking of singing and dancing, feast your eyes on the production numbers. “Honeymoon Hotel” has Keeler and Powell getting married and spending their first night together in a hotel filled with honeymooners. In true precode fashion, the sex is more than alluded to, the women are scantily clad, and Billy Barty, the most successful midget in movies, plays a not-so-innocent child who follows the chorus girls around the corridors. “On a Waterfall” has to be seen to be believed. From a simple stage duet by Keeler and Powell, an entire soundstage full of water slides and an enormous pool emerge. Berkeley’s famous overhead camera shots show the mermaids move into the kaleidoscopic formations for which he was known. The cameras take us underwater, too, for some sexy shots. Clearly, these  prologues cannot be justified by the story. Only the magic of movies can present these types of images to a large audience at one time. They simply are their own source of wonder. The final production number, “Shanghai Lil” features my favorite dance by Keeler. Her eccentric tapping style perfectly fits Cagney’s, and they carry this number off beautifully. You can see it here.

prologues cannot be justified by the story. Only the magic of movies can present these types of images to a large audience at one time. They simply are their own source of wonder. The final production number, “Shanghai Lil” features my favorite dance by Keeler. Her eccentric tapping style perfectly fits Cagney’s, and they carry this number off beautifully. You can see it here.

Footlight Parade combines screwball comedy's wisecracking, scattershot dialogue with the psychedelic fever dreams of Busby Berkeley and some of the best actors of the 1930s to produce a film of enduring appeal and subtle social commentary. This film is essential viewing for every film enthusiast. l

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home