The Conformist (Il Conformista, 1970)

The Conformist (Il Conformista, 1970)Director: Bernardo Bertolucci

The Conformist is a film that has attained legendary status. A beautiful and surprisingly assured work by preeminent director Bernardo Bertolucci and equally respected cinematographer Vittorio Storaro when they were just in their 20s, The Conformist dropped quickly from sight after its rave reception at several film festivals. It only got a very, very limited run in the United States after the likes of Francis Ford Coppola urged Paramount to release it. The film also was scarce in its native country because of its depiction of the popularity of fascism in 1930s Italy.

At long last, Paramount has released a DVD of The Conformist, including a three-part special on the making of the film that includes interviews with Bertolucci and Storaro. This DVD, the most anticipated foreign-film release of the year, does justice to the film (which I saw on the big screen early in 2006) and sheds light on its sometimes frustratingly oblique approach.

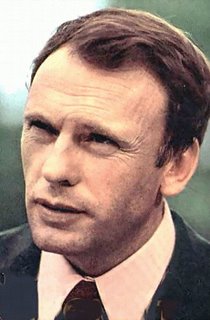

The title character is Marcello Clerici (Jean-Louis Trintignant). We first meet him in a hotel room fitted out with ornate, antique furniture, surrounding his nervous movements and '30s private-eye appearance with traditional elegance. Already there seems to be some sort of disconnect between Marcello and his surroundings. Marcello soon is shown riding in a car with Manganiello (Gastone Moschin), an affably viperish operative for the Italian fascists. From here on, most of the film is shown in flashback as we watch Marcello move from privileged childhood to fledgling spy for the Italian government.

Marcello is friends with a blind fascist named Italo (José Quaglio). This not-very-subtle symbol for Italy under Mussolini broadcasts fascist propaganda on the radio and introduces an eager Marcello to the Colonel (Fosco Giachetti), who can help Marcello realize his ambitions. Marcello enters a monumental building, his tiny figure like an ant moving across a vast marble expanse. He enters the wrong room for a brief moment and catches a glimpse of a ranking fascist seducing a woman in mourning attire who is laying across his desk. Marcello's and the woman's eyes meet for an instant. Excusing himself quietly, Marcello goes on to the Colonel's office.

Marcello offers to try to infiltrate the antifascist movement through his former philosophy professor, a middle-aged man named Quadri (Enzo Tarascio) who is a self-exile in Paris. The Colonel knows Marcello is not a true believer, nor is he being bribed to work for the fascists. The Colonel cannot guess Marcello's motive for signing on to the cause, but he willingly accepts. When the Colonel learns Marcello is soon to be married, he considers a honeymoon in Paris as the ideal cover.

A happy Marcello goes to dine with his fiancee Giulia (Stefania Sandrelli) and her mother (Yvonne Sanson). Giulia is a simple-minded bourgeois whom Marcello chose because of her sheer ordinariness, her good looks, and her sexually eager nature. He teases her about their

honeymoon destination, and she teases him with an invitation to love right on the carpet of the sitting room. (This invitation must have been the inspiration for a similar offer from Angelica Huston to Jack Nicholson in Prizzi's Honor.) Giulia's black-and-white striped dress and the shadows created by the light coming through the blinds suggest a noirish atmosphere, but moreso a rigid geometry surrounding Marcello. His desire, like all fascists, is for strict order.

honeymoon destination, and she teases him with an invitation to love right on the carpet of the sitting room. (This invitation must have been the inspiration for a similar offer from Angelica Huston to Jack Nicholson in Prizzi's Honor.) Giulia's black-and-white striped dress and the shadows created by the light coming through the blinds suggest a noirish atmosphere, but moreso a rigid geometry surrounding Marcello. His desire, like all fascists, is for strict order.The Clericis' train makes a stop before they proceed to Paris. Marcello moves quickly along a dock, moving behind a painting at an outdoor market of a boat on a dockside, and emerging from behind the painting into the exact scene it depicted. Marcello meets Manganiello in a boathouse where the older fascist is being entertained by a red-haired whore. Manganiello sends her over to greet his friend. He takes one look at her and hugs her close. Marcello is given a handgun, and in a move that frightens Manganiello, points it straight at the him. Marcello then assumes a couple more attitudes with the gun, practicing not only how to hold and aim it, but also to look like a man who holds, aims, and fires guns. Instead of infiltrating the Quadri antifascist cell, he is ordered to kill the man.

Once the newlyweds are ensconced in their hotel room (the room we saw in the opening scene), Marcello phones Quadri to suggest a meeting for old times' sake. Quadri invites the Clericis over for tea. They are greeted at the door by a large dog and Anna Quadri (Dominique Sanda). Marcello seems thunderstruck by her, and we get the distinct impression that they know each other. In fact, Sanda played the woman in black and the whore. She is clearly the woman of Marcello's dreams, and he spends the rest of his trip to Paris pursuing her.

For her part, Anna distrusts Marcello and has her eye on Giulia. The two women go out shopping for gowns they can wear dancing, and while they prepare for the evening out, Anna has sexual contact with an initially angry and then willing Giulia. Immediately after this encounter, Anna goes to Marcello and falls into his arms. Her interest in Marcello, however, is to plead with him to spare her life and that of her husband.

For her part, Anna distrusts Marcello and has her eye on Giulia. The two women go out shopping for gowns they can wear dancing, and while they prepare for the evening out, Anna has sexual contact with an initially angry and then willing Giulia. Immediately after this encounter, Anna goes to Marcello and falls into his arms. Her interest in Marcello, however, is to plead with him to spare her life and that of her husband.Manganiello has tried to contact Marcello, but having lost his taste for his task because it puts Anna in danger,

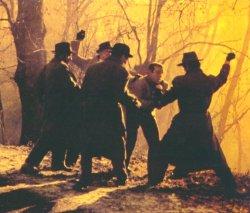

Marcello dodges him. Finally, there can be no more delay. We return to the present, as the two men follow the Quadris up a snow-covered mountain road as they make their way to their vacation home outside of Paris. The Quadris' way is blocked by a car that has skidded in front of them, the driver apparently stricken. Manganiello blocks their way from behind. Against Anna's cautions, her husband leaves the car to check on the other driver. At that moment, a number of trench-coated fascists - Marcello's and Manganiello's coconspirators - emerge from the surrounding woods and set upon Quadri with knifes in a scene reminiscent of the

Marcello dodges him. Finally, there can be no more delay. We return to the present, as the two men follow the Quadris up a snow-covered mountain road as they make their way to their vacation home outside of Paris. The Quadris' way is blocked by a car that has skidded in front of them, the driver apparently stricken. Manganiello blocks their way from behind. Against Anna's cautions, her husband leaves the car to check on the other driver. At that moment, a number of trench-coated fascists - Marcello's and Manganiello's coconspirators - emerge from the surrounding woods and set upon Quadri with knifes in a scene reminiscent of the  assassination of Julius Caesar. Anna flees her car and spies Marcello in the backseat of the rear car. She bangs on his window, wailing like an animal for his help. He might have helped her or mercifully shot her to end her misery, but he sits by and does nothing. She runs off and is stalked and shot dead in a scene of utter brutality.

assassination of Julius Caesar. Anna flees her car and spies Marcello in the backseat of the rear car. She bangs on his window, wailing like an animal for his help. He might have helped her or mercifully shot her to end her misery, but he sits by and does nothing. She runs off and is stalked and shot dead in a scene of utter brutality.The film fast-forwards to the end of the war. Marcello plays with his young daughter as the household listens to the radio in their house in Rome as news of Mussolini's arrest and demonstrations throughout the city rings out. Giulia reminisces regretfully about the Quadris, but forgives Marcello for his fascist loyalty. "It was good for your career," she says in unreflexive, bourgeois justification. Italo calls Marcello for help, and Marcello grabs his coat, though it is dangerous for known fascists to be in the streets. Giulia tries to stop him, but he says he must go, that he wants to see what it looks like when a dictatorship falls. On the street, he has an encounter that upsets everything he ever believed about himself and turns him into a raging lunatic. His fascist control is gone from inside him as well as from the city that swallows him up in the night.

So what is it that drives Marcello? What is it that he believes about himself that leads him to pursue social conformity in spite of the irrational urges that spill forth when he is confronted with Anna and her lookalikes? We are led to believe that a homosexual encounter Marcello had when he was 14 that resulted in him shooting his seducer has made him feel different. Bertolucci and Storaro state in the DVD interviews that it is the shooting that set him apart as a killer in his own mind, but I think there is much more going on than that. The man who seduced him was his chauffeur, and this man rescued the young Marcello from the tauntings of his schoolmates, who had attempted to remove his pants. So, we see right away that he doesn't fit in, perhaps because of his family's wealth, perhaps because he has betrayed some hint of homosexual longing.

Before Marcello marries Giulia, he goes with his morphine-addicted mother (Milly) to see his father (Giuseppe Addobbati), who has been institutionalized in an insane asylum (in fact, a massive building constructed at Mussolini's orders). It would certainly not surprise me if Marcello was a little touched himself, or at the very least, fearful of being overtaken by the madness that felled his father and drove his mother's addiction. Those who seek to fence out the irrational will naturally gravitate to the safe, narrow tracks of society's rules, and certainly to fascism. (It's easy to see how the neoconservatism of modern times that bears a strong resemblance to fascism might have arisen from the sexually and politically open 1960s and '70s.)

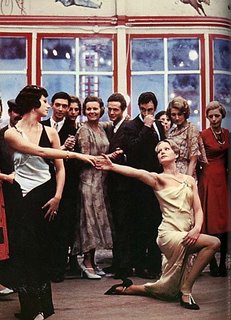

Marcello's attitude toward women is at least as repressed as his other urges. When the Quadris and Clericis go out for Chinese food and dancing, Anna asks Giulia to dance. The two do a seductive tango that disturbs the conventional couples on the dance floor and scandalizes Marcello. Quadri is content with their behavior: "They both look so pretty." He has accepted the bisexual Anna as she is, whereas Marcello holds his wife in contempt and thinks nothing of abandoning her on their honeymoon for Anna. While he may feel an irresistible regard for Anna, it is, perhaps, more threatening to think that his conventional wife is more sexually liberated that he could have imagined. As the ultimate irrational in a man's psyche, women must be as predictable as possible for the man Marcello desperately wants to become.

Marcello's attitude toward women is at least as repressed as his other urges. When the Quadris and Clericis go out for Chinese food and dancing, Anna asks Giulia to dance. The two do a seductive tango that disturbs the conventional couples on the dance floor and scandalizes Marcello. Quadri is content with their behavior: "They both look so pretty." He has accepted the bisexual Anna as she is, whereas Marcello holds his wife in contempt and thinks nothing of abandoning her on their honeymoon for Anna. While he may feel an irresistible regard for Anna, it is, perhaps, more threatening to think that his conventional wife is more sexually liberated that he could have imagined. As the ultimate irrational in a man's psyche, women must be as predictable as possible for the man Marcello desperately wants to become.The central metaphor of this film is Plato's cave. When Marcello and his old professor meet, Marcello reminds Quadri of the lesson about the prisoners chained to face the back of a cave, seeing only the shadows of the objects moving behind them. As in Plato's cave, Marcello himself seems to be a shadow. This is emphasized when Marcello's shadow on the wall of Quadri's study vanishes when the professor opens the window blinds.

Like all of Bertolucci's films, The Conformist is deeply sensual. Storaro provides sumptuous visual effects that make the film appear to be a dream inside a dream. Bertolucci says in the DVD interview that he always thought it was a shame that films had to be edited from the daily rushes. For him, the rushes represent the unfiltered creativity of the entire enterprise. Nonetheless, Storaro and film editor Franco Arcalli manage to keep an impressionistic, almost surrealist feel even as they create a mood and narrative drive that build from illusion to horror. Lead actor Jean-Louis Trintignant is just a little too cryptic for my tastes. He doesn't suggest depths under still waters, and I think that would have helped this film in its first half. Marcello is a part made for Matt Damon. As heretical is this may seem, Alberto Moravia's novel on which this film is based may be due for a reinterpretation. Of course, no one should, or will, ever remake The Conformist. l

6 Comments:

At 9:01 PM, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

Great review, Marilyn. It was very interesting to hear a woman's perspective. I watched the DVD last night and was blown away. It seems that there is so much current cinema that borrows from this one film. Surely Mingehlla was thinking of the brutal woods scene when he was filming Jude Law's demise in "Cold Mountain"? The tango scene reconstructed by Penelope Cruz and Charlize Theron in "Head in The Clouds"? Probably so many more, there's a multitude to steal from. Happy New Year!

At 11:09 AM, Marilyn said…

Marilyn said…

Considering that The Conformist has, up to now, been available primarily through film classes (which I how I saw it first), I wouldn't be at all surprised if you were right.

Happy New Year to you, too!

At 9:54 PM, Roderick Heath said…

Roderick Heath said…

I've not seen this film, but I read some of Alberto Moravia's novel. The fundamental flaw of Marcello's motivation comes from the source. Moravia puts in what he thinks are all the pieces, but his sense of pstchology is not convincing. It was ultimately that he failed to convince me that he knew what was going on in Marcello's mind and soul that caused me to stop reading it.

At 10:06 PM, Marilyn said…

Marilyn said…

Rod - That is the weakness in the movie, too, but there is enough going on around Marcello to suggest some motivation. One problem is the desire to turn people into symbols, which may be what went on in the novel and what happens to a not small extent in the movie. This is a fundamental problem with artists interested in national identity, one that can also be found in Brian Friel as reflected in Dancing at Lughnasa (which I reviewed on this site). Bertolucci was, of course, very attracted to symbolism, especially in his youth.

At 10:50 AM, movie links said…

movie links said…

I was lucky enough to see this one in a theater just two months after seeing it first. If you have the chance, go see it on a big screen.

At 10:53 PM, junayad khan said…

junayad khan said…

Hi,

I am very happy that I got nice information about how to Cure addiction from your blog and I hope you will write more about it.

Thanks

Post a Comment

<< Home