1900 (Novecento, 1976)

1900 (Novecento, 1976)Director: Bernardo Bertolucci

By Roderick Heath

In the mid 1970s, Bernardo Bertolucci was a figure with the financial clout and artistic eminence to produce a hugely ambitious flop. But that flop, 1900, is such a totemic work that it is impossible to dismiss, as it attempts to revive the mammoth dimensions of presound epic cinema, like Abel Gance’s Napoleon and Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen, and invest it with a kind of socialist epic mythology. It also illustrates the schism between the standout features of Bertolucci as a director—a great portrayer of sensuality and psychology, and a committed political artist who can never quite reconcile the two perspectives.

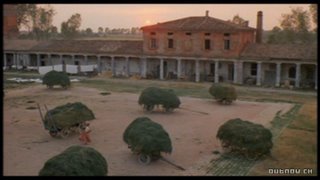

The film begins a huge ellipse as the Allies are winning the war and partisans are mopping up the remnants of Italian fascism. Field-labouring women scooping hay in shots framed like classical landscape artists spy the escaping Atila (Donald Sutherland) and his wife Regina (Laura Betti), and chase after them with pitchforks. The sight of this middle-aged pair crying for each other, farm implements jutting from their bodies, is horrific and demands sympathy. One of the peasant boys decides to march into the house of the local padrone (landlord), Alfredo Berlinghieri (Robert De Niro) and take him prisoner. Alfredo, caught at breakfast, pleasantly agrees, “Long live Stalin!”

1900 contrasts Alfredo with Olmo Dalco (Gerard Depardieu). Both men were born on the night Giuseppi Verdi died (January 27, 1901), and are tied together by life on the Berlinghieri estate. Each grows up in the care of their grandfathers—Alfredo, with the grand old padrone (Burt Lancaster), and for Olmo, Leo (Sterling Hayden), patriarch of the peasants who are nightly locked in their barn. The two old bulls have a prickly friendship, united by their earthy sense of nature, sex, and socializing even as they are separated by class and resentment. Olmo never discovers who his father is. Alfredo knows his all too well—the cold, callow, money-grubbing younger son of the padrone, Giovanni (Romolo Valli). Elder son Ottavio (Werner Bruhns) has fled the estate to lead a bohemian, cosmopolitan life.

Casting Lancaster as the padrone ties this film thematically and chronologically to Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard, as that film’s aspiring liberal Italy is dying. The padrone gives Alfredo a buffer from his crass parents, but hangs himself when he can’t achieve an erection in the hand of a girl. Mechanization destroys the bonds of the landlord-peasant relationship; Giovanni’s entitled greed doesn’t help. The native wisdom of Leo—he won’t let any Dalco become a priest, the ultimate freeloader—agrees with the socialist ideals that excite the labourers to strikes and revolts. He lectures Olmo in his creed as the boy marches down the long dining table, stepping over the eating families’ plates of food, a vision of the gritty vitality of communal life. Olmo and

Alfredo (played as youths by Roberto Maccanti and Paolo Pavesi, respectively) taunt and entertain each other with the dirty panoply of boyish obsessions and character tests. Olmo’s great feat of bravery is to lay between railroad tracks as a train (a recurring symbol of tidal history) rushes over him, which Alfredo cannot at first manage, and no one sees it when he does.

Alfredo (played as youths by Roberto Maccanti and Paolo Pavesi, respectively) taunt and entertain each other with the dirty panoply of boyish obsessions and character tests. Olmo’s great feat of bravery is to lay between railroad tracks as a train (a recurring symbol of tidal history) rushes over him, which Alfredo cannot at first manage, and no one sees it when he does.World War I precipitates the great rupture in Italian society that has been building. Olmo fights and Alfredo is commissioned, but kept home by his father’s influence. Olmo returns to find the number of workers reduced, machines encroaching, and the estate now run by foreman Atila, who poses as a simpatico fellow veteran. With the prodding of his personal Lady Macbeth, Regina, Atila soon becomes a fascist bigwig. Giovanni and other landowners form a fascist chapter in response to their inability to evict peasantry, who successfully resist the cavalry with nonviolent tactics.

Olmo and Alfredo resume their edgy friendship, Alfredo regarding them both as free spirits, though he is torn between temptations of power and the intentions of his liberality. Bertolucci tries to demonstrate how Alfredo is a decent man imprisoned by position, his ability to force his wishes on other people incidentally malevolent. Alfredo and Olmo go into the city to visit Ottavio, and get sidetracked with a prostitute, Neve (Stefania Casini). When the three of them are in bed together (as usual, Bertolucci suggests homoeroticism, but never gets around to portraying it), Alfredo forces Neve to drink, which sets her off in a violent epileptic fit between the two men whose penises she’s grasping.

Olmo has a crush on Anita (Anna Henkel), an educated girl who has come to work on the estate and act as the peasant’s schoolteacher. They marry and have children, and Anna starts a community school through the developing socialist infrastructure. Alfredo meets Ada Paulhan (Dominique Sanda, tres bon), a half-French orphan (her parents perished guiding rich tourists on a mountaineering expedition; “They died as they lived—beyond their means.”) who lives with Ottavio and whom he assumes is his mistress, not yet knowing his uncle is homosexual. Ada’s a loopy, capricious poseur and muse who occasionally fakes blindness and writes awful poetry. Alfredo finds her wonderful.

Alfredo, Ada, and Ottavio live out a bohemian fantasy, snorting cocaine and gaily dancing. Ada and Alfredo and Olmo and Anita drink together in bar set up in a barn, Afredo begging that the four of them will always remain the same. Two deflowerings are instantly precipitated. Ada and

Alfredo screw amidst the hay bales, Alfredo stunned that Ada is a virgin. The innocent solidarity of the socialists is killed when Atila and the fascists burn the school, killing three old peasant men Anita had been teaching to read. As the communists rally, Atila, being fitted for a black uniform, demonstrates to his awed fellows the attitude required of a fascist; he straps a cat to the wall and crushes it with a running head-butt.

Alfredo screw amidst the hay bales, Alfredo stunned that Ada is a virgin. The innocent solidarity of the socialists is killed when Atila and the fascists burn the school, killing three old peasant men Anita had been teaching to read. As the communists rally, Atila, being fitted for a black uniform, demonstrates to his awed fellows the attitude required of a fascist; he straps a cat to the wall and crushes it with a running head-butt.Atila and Regina are the film’s nexus of evil (Sutherland managed to freak himself out viewing his acutely perverse performance). Giovanni dies and Alfredo inherits the estate. Despite Olmo’s earnest, faintly menacing warning, Alfredo cannot rid himself of Atila, a deep-rooted cancer. Regina’s crush on Alfredo (they were briefly lovers; in one scene, Alfredo tries to orgasm Regina with the butt of his rifle, a moment as ribald as it is symbolic) makes her loathe Ada. Atila and Laura’s machinations extend to murdering a woman for her house, and, at Alfredo and Ada’s wedding, drunkenly raping and beating to death a young boy. When the body is found by searching wedding guests, Olmo is close by. Spurred by Atila, they mercilessly beat him, and Alfredo won’t stop it. Is he afraid of Atila? Or glad to see his judgmental pal receive a hiding? Either way, Olmo’s life is only saved when another peasant confesses. Anita dies, leaving Olmo to care for several small children. (Even at 300 minutes, 1900 is missing pieces. We see neither Anita and Olmo’s wedding nor her death, and supporting characters in the film often disappear.)

Ada is distanced from Alfredo—Ottavio has vowed never to return at all—because of his poor response to fascist courtship. Ada relies on Olmo for emotional support even as he resents her trying to tutor his kids. Perhaps the film’s best scene comes when Alfredo and Ada row fiercely in a skid row tavern, Alfredo accusing Ada of having an affair with Olmo, then infuriated by her calling him a fascist. Alfredo recognizes Neve when she enters the tavern; her laughing acceptance of life’s caprices briefly reunites the troubled couple.

As Italy enters World War II, Alfredo’s attempts to fire Atila prove impotent. Atila massacres “partisans” in a miniature concentration camp set up in the centre of the villa. Olmo goes into hiding, and does not reappear until war’s end. Atila and Regina, after the pitchforking, are both duly shot by a kangaroo court, with Alfredo to be

next for his collaboration. Bertolucci tries to celebrate the victory for the Italian workers in scenes staged to resemble a ’60s happening or Stalinist rally, with narrative becomes imagistic parade. Eventually, with Solomonian wisdom, Olmo talks the partisans out of executing Alfredo because all they have to do is declare that the padrone is dead—not the inhabitant of the role, but the role, the title, the idea. Alfredo, up till now accepting and life-weary, manages a stiff-necked response to Olmo’s rescue. Just as when they were kids, they begin wrestling in enraged love.

next for his collaboration. Bertolucci tries to celebrate the victory for the Italian workers in scenes staged to resemble a ’60s happening or Stalinist rally, with narrative becomes imagistic parade. Eventually, with Solomonian wisdom, Olmo talks the partisans out of executing Alfredo because all they have to do is declare that the padrone is dead—not the inhabitant of the role, but the role, the title, the idea. Alfredo, up till now accepting and life-weary, manages a stiff-necked response to Olmo’s rescue. Just as when they were kids, they begin wrestling in enraged love.1900 is a structural chimera, trying to fuse Shakespearean drama, Brechtian epic theater, socialist realism, and propagandist melodrama. Bertolucci tips his hat to Visconti not only via The Leopard, but also by borrowing thematic value from Visconti’s own rise-of-fascism parable, The Damned, following its lead in quoting the plots of MacBeth and King Lear, and also its portrayal of fascism as indivisible from a psychologically rooted adoration of raw force, sexual degeneracy, and gross greed. This also echoes Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salo (1975). As in Pasolini’s oeuvre, 1900 contrasts free sexuality in his bohemians (Ottavio cavorting with his male models) and workers (Olmo gives Anita earth-shaking head) with the savagery of fascist sexuality, in Atila’s child rape and Regina’s voracity that conceals an incapacity for orgasm. Alfredo’s occasional displays of cruelty in bed reflect his temptation to the extreme ego-fulfillment of fascism.

1900 is at its best when not concentrating on politics. The complexities that compile in Ada and Alfredo’s marriage, which breaks up because of her fear she will be held guilty with Alfredo at the war’s end, but already long poisoned by the spectacle of his weakness, successfully dovetails the themes. The multinational cast demanded by complex funding arrangements, but allowing a capricious pick-and-choose of international talent, meant that the soundtrack is never entirely comfortable. In the English dub ( most of the smaller parts are Italian), things often go spaghetti western, yet watching the Italian version loses the original interpretations by De Niro, Lancaster, Hayden, et al. De Niro, in his career’s golden era, is at his youthful, supple best. He

ages far more convincingly in the film than he has in real life. The film has slow stretches, but always seems to have some virtuoso set-piece in store, from the sweeping early sequences that show off Bertolucci’s gift for camera movement (aided by the Velazquez-toned photography of Vittorio Storaro), to give a sensation of drifting through countryside and time, to that vivid final scene, both distressing and weirdly comic, a glimpse of a future where Alfredo and Olmo are old men, still fighting and sticking by each other. Olmo escorts Alfredo to his last act on earth, lying across the railroad, head about to be flattened by a train. Like his grandfather, Alfredo suicides—a tired, sympathetic remnant of a superfluous class clucked over with indulgent dismissal by Olmo. l

ages far more convincingly in the film than he has in real life. The film has slow stretches, but always seems to have some virtuoso set-piece in store, from the sweeping early sequences that show off Bertolucci’s gift for camera movement (aided by the Velazquez-toned photography of Vittorio Storaro), to give a sensation of drifting through countryside and time, to that vivid final scene, both distressing and weirdly comic, a glimpse of a future where Alfredo and Olmo are old men, still fighting and sticking by each other. Olmo escorts Alfredo to his last act on earth, lying across the railroad, head about to be flattened by a train. Like his grandfather, Alfredo suicides—a tired, sympathetic remnant of a superfluous class clucked over with indulgent dismissal by Olmo. l

4 Comments:

At 12:45 PM, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

There are so many things to say about Novecento.

One of the weirdest things is that Novecento, the most optimistic movie on the

history of Italy in the 1900, and Pasolini's Salò, the darkest view on the

same subject, were shot in the same months in two nearby regions of the north

country.

Bertolucci and Pasolini hardly spoke to each other by that time, although

Bertolucci learnt his trade on the set of Pasolini's debut movie, Accattone,

where he was a young assistant director. They eventually smoked the peace pipe

during the shooting of those two movies, when a soccer match took place, in

Cremona (if memory serves me) between their two film crews. Can't recall who

won, though.

More soon, hopefully.

Giuliano

At 8:12 PM, Tom Paine said…

Tom Paine said…

I believe Anita was played by Stefania Sandrelli.

At 8:54 AM, Marilyn said…

Marilyn said…

Anna Henkel played Anita.

At 6:57 PM, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

Stefania Sandrelli and Anna Henkel both played characters called Anita in the film: Sandrelli played the older Anita, Olmo's wife, in the first half of the film, and Henkel played the daughter of Anita and Olmo, who was also named Anita, in the second half of the film.

Anyway, thanks for writing that post, it was excellent: I've been searching for detailed comments about 1900 on the web recently and this is one of the best articles I've found.

Post a Comment

<< Home