Be Here to Love Me: A Film About Townes Van Zandt (2004)

Director: Margaret Brown

Music documentary is a specialized and difficult film genre in which to dabble. In most cases, the music is the most interesting aspect of the musician or group being profiled. The music documentarian, therefore, essentially has two choices—make a concert film that puts the music and the musician’s magnetic persona center stage or choose a subject with such an interesting life or at such an interesting juncture in history that the visual experience will at least equal the experience of simply listening to a CD.

Among the successes of the genre are Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz (1978), which records the last live concert of The Band; the Maysles brothers’ Gimme Shelter (1970), about the Rolling Stones’ disastrous concert at Altamont, California; Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock (1970); and Sam Jones’ I Am Trying to Break Your Heart (2002), about the recording of Wilco’s fourth album. Each of these documentaries covered a live experience, which gave the directors the advantage of being able to react to events as they unfolded.

Even when a director must rely primarily on archival footage, the results can be inspired. Bob Smeaton’s Festival Express (2003), about the rock festival train that brought Janis Joplin, The Grateful Dead, and other top performers to cities across Canada in 1970, benefited from great candid films of the time and a sense of fun about the experience Smeaton was able to capture. Smeaton certainly got lucky by having an abundance of source material from which to choose. Margaret Brown, on the other hand, set herself the challenge of documenting the life of a musician who had cult status even in his own lifetime and is almost unknown today. The pickings must have been a lot slimmer for her.

Brown took filmed concert footage, archival photos and home movies, and live interviews with Van Zandt’s contemporaries and loved ones, and presented them in a sometimes interesting, sometimes tricked-up visual display. Brown explains her finished product in this way in her director’s note:

“Guy (Clark, a close friend of Van Zandt’s) told me that Townes’ songs work because of negative space. It’s the holes you leave, he said. I wanted Be Here to Love Me to work in the same way—not by spelling out every detail of his life, but by presenting details that are often more telling than dates or facts. By juxtaposing voiceover with performance, traveling in time to present effect before cause, and letting the audience make up their own mind about whether Townes’ decision to drop his family and most trappings of normal life to ‘get a guitar and go’ was worth it, I felt that this would create a more emotionally true film.”The fact that this statement of purpose is so pretentious and presumptuous regarding the value of dates, facts, and the audience's right to decide whether Van Zandt’s choices were worth it (To whom? Townes? His wives and children? Music?) shows that even Brown recognizes that her film doesn’t really work. It is unnecessarily vague when a few title cards or voiceovers with basic information would have been enlightening without ruining the creative flow. Worst of all, by failing to get closer to the heart of Van Zandt, Be Here to Love Me ends up sullying his legacy with tragic artist clichés that never abate.

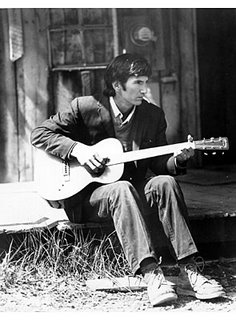

Who was Townes Van Zandt? I’d never heard of him. The official website of Be There to Love Me quotes Steve Shelley of Sonic Youth about Townes: “He’s not really a country singer, you wouldn’t call him a blues artist, he’s not quite a folk singer, he doesn’t exactly write pop songs, so what is he? He does not fit neatly into a category, and to me, that is what sets him apart as a great artist.” I found that the concise description from my sweetie, a 54-year-old ex-hippie, said it all: “He was the Woody Guthrie of my generation.” Indeed, Van Zandt's life and work bear a strong likeness to Guthrie's.

Who was Townes Van Zandt? I’d never heard of him. The official website of Be There to Love Me quotes Steve Shelley of Sonic Youth about Townes: “He’s not really a country singer, you wouldn’t call him a blues artist, he’s not quite a folk singer, he doesn’t exactly write pop songs, so what is he? He does not fit neatly into a category, and to me, that is what sets him apart as a great artist.” I found that the concise description from my sweetie, a 54-year-old ex-hippie, said it all: “He was the Woody Guthrie of my generation.” Indeed, Van Zandt's life and work bear a strong likeness to Guthrie's.

Van Zandt was a troubled alcoholic and polydrug abuser (glue was his first high) from a well-to-do Forth Worth, Texas, family who had the gifts of poetry and music. He was influenced by Lightnin’ Hopkins and Bob Dylan and combined a folk-bluesy style with serious lyrics to create songs and performances that touched listeners deeply. Perhaps his best-known song is “Pancho & Lefty,” recorded by Emmylou Harris and made into a music video and top single by Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard. Van Zandt died in 1997 at the age of 52, leaving behind three children, three wives, and a lot of great songs that are seldom played today.

The film concentrates on the more grisly aspects of his life. He dropped off the porch of a four-story building supposedly to experience the sensation of falling. His parents, worried about his suicidal inclinations, allowed doctors to apply insulin shock treatments to him for three months that wiped out his childhood memories. He married a traditional girl who was shocked when the first song he wrote after they were married was “Waiting to Die.” “Here I was, a 20-year-old newlywed thinking he’d come out with a love song for me,” Jeanene said. Brown did not think it was important to mention how long they were married, when they divorced and why, and how many of Townes' children were hers. We are just left with the information that he was gone on the road a lot, and that was probably the reason she got fed up. I learned from other sources that it took her 16 years to call it quits.

We get the idea that Van Zandt wasn’t much fun to be around from his son J.T. and his second wife Cindy. A six-year-old J.T. apparently begged to return to Jeanene from a two-week trip to see Townes he had been looking forward to tremendously. Cindy, when asked in archival footage what it was like to live with Townes, got a grim look on her face and said that it sucked. She laughed immediately and changed her tune, but the truth was already out.

His best friend Guy Clark said Townes was always hitting on his wife Susanna. Clark, still a hard-living musician almost certainly drunk during the film's interviews, was probably a major contributor to Van Zandt’s sobriety problems through mere association. Other enablers were Kevin and Harold Eggers, record producers who didn’t do much to advance Van Zandt’s career and seem as messed up as he was. Renowned music producer John Lomax III was ready to take on Van Zandt, but Townes messed that up.

So what are we left with? Some nice footage of Townes singing some great songs. Some stars, like Emmylou and Willie, paying tribute to Van Zandt’s music while not really seeming to know anything about him. Some intimates whose affection for Townes doesn’t really connect with us.

The only people in the film who really moved me were Van Zandt’s children. J.T., the oldest, seems to have come to terms with his father, though he doesn’t buy the idea that artists need to give up everyone for their art. Teenaged Will seems eternally sad and haunted. Young Katie Belle sings to her father’s records as her only living legacy of him.

I’m glad I saw this movie because it gave me a taste of a musician whose work has the touch of genius. I could have been spared the troubled artist line this film bangs home like a two-year hangover; it does not make the life of Townes Van Zandt interesting, but rather just another train wreck from the world of music. l