Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus (2005)

Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus (2005)Director: Andrew Douglas

Since the discovery of the New World, Europeans have been fascinated by American rustics. Indeed, Benjamin Franklin practically made a career in France out of being an "authentic" American. So it seemed natural for English director Andrew Douglas to want to go out and make a film about the American hillbillies and rednecks he envisioned after he encountered Jim White's debut album "Wrong-Eyed Jesus (Mysterious Tale of How I Shouted)." BBC Arena was more than willing to put up the funds to produce Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus. Fascination with the bloodlines and musical heritage that run between the old families of the Old South and the even older families of Merrie Olde England make such a film an audience pleaser on the right side of the Atlantic. Throw in some decent country music, and you may have a film that people around the world will respond to.

Douglas uses White as the guide through the heart of the trailer-trash, Pentacostal, backwoods, musical South. To equip them properly for their journey, White secures a rusted boat of a car circa 1970 and buys a statue of Jesus to put in its trunk. As White drives Douglas and camera crew through lands that time forgot, he talks of his own spiritual feelings and desire to belong to the South, where he grew up but not where he was born or where he spends most of his time. He's fond of metaphors, and, for this writer, uses them to distraction.

Douglas uses White as the guide through the heart of the trailer-trash, Pentacostal, backwoods, musical South. To equip them properly for their journey, White secures a rusted boat of a car circa 1970 and buys a statue of Jesus to put in its trunk. As White drives Douglas and camera crew through lands that time forgot, he talks of his own spiritual feelings and desire to belong to the South, where he grew up but not where he was born or where he spends most of his time. He's fond of metaphors, and, for this writer, uses them to distraction.They pass trailers by the dozens, towns that begin and end in the span of a five-minute drive, and some homes on stilts in the middle of swampland. The camera travels across water (shades of Jesus!) and lands in front of a house in the middle of a lake, its porch skimming the waters. On it stands the Handsome Family, who perform a song. This is the first of many musical interludes that seem to want to make a connection between the land and the music, but usually come off as too precious by half. Another clear miss is a haunting rendition of "Amazing Grace" played on a saw by Melissa Swingle as she sits on a blanket in the trunk of a car parked in the middle of a wood. Following this song, Douglas films her sitting in the back seat of the car telling a fairly pointless story about two of her relatives laughing at their grandmother's funeral.

Not all of the musical moments misstep, however. A Kentucky coal miner and banjo picker provides some touches of authenticity with his round, weathered face and old timey rendition of "Rye Whiskey." A finely crafted duet of "First There Was" by Johnny Dowd and Maggie Brown moves quietly between Dowd sitting in a barber shop and Brown curling a woman's hair in the adjacent beauty salon. Indeed, the male and female worlds seem to separate into two experiences as filmed by Douglas - heartache for women and hard work and violence for men. Only in church and in juke joints do the two worlds come together in a variation of the same kind of ecstatic, emotional release these hard-against-it people need to keep head and heart together.

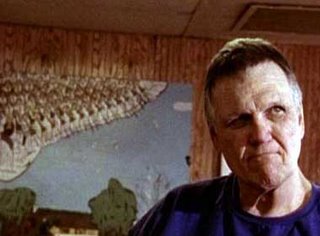

Not all of the musical moments misstep, however. A Kentucky coal miner and banjo picker provides some touches of authenticity with his round, weathered face and old timey rendition of "Rye Whiskey." A finely crafted duet of "First There Was" by Johnny Dowd and Maggie Brown moves quietly between Dowd sitting in a barber shop and Brown curling a woman's hair in the adjacent beauty salon. Indeed, the male and female worlds seem to separate into two experiences as filmed by Douglas - heartache for women and hard work and violence for men. Only in church and in juke joints do the two worlds come together in a variation of the same kind of ecstatic, emotional release these hard-against-it people need to keep head and heart together. Perhaps the best parts of this film for me are the musing of Georgia-born writer Harry Crews. He provides one of the best descriptions of the heart of the South I've heard simply by explaining what the people in his town did when the Sears Roebuck catalog arrived in the mail. First, he points out that all of the people in the catalog were perfect, "with all the fingers they were entitled to," and all the people in his town were maimed and marked from physical labor, brawling, and disease. Nonetheless, the townspeople gave the Sears people "lives" like their own - pairing a female model on page 33 with a male model on another page and imagining an affair between them that the female's daddy on page 107 was going to end using a rifle. The South is about family, and at least among the people Douglas meets, about troubled family life. It's easy to see why the sacrificed Son of God would seem a familiar and living being to these people.

Perhaps the best parts of this film for me are the musing of Georgia-born writer Harry Crews. He provides one of the best descriptions of the heart of the South I've heard simply by explaining what the people in his town did when the Sears Roebuck catalog arrived in the mail. First, he points out that all of the people in the catalog were perfect, "with all the fingers they were entitled to," and all the people in his town were maimed and marked from physical labor, brawling, and disease. Nonetheless, the townspeople gave the Sears people "lives" like their own - pairing a female model on page 33 with a male model on another page and imagining an affair between them that the female's daddy on page 107 was going to end using a rifle. The South is about family, and at least among the people Douglas meets, about troubled family life. It's easy to see why the sacrificed Son of God would seem a familiar and living being to these people.And it's easy to see that Jim White's real quest is not to be Southern in his blood, as he claims, but to have family ties that bind. This fact, I think, is what saves this film from its considerable shortcomings - its unmotivated artiness (including its last, utterly false shot), Diane Arbus-like portraits of its subjects, and the complete absence of African Americans and a mention of the obvious link between Pentacostal worship and African-inspired rituals of the Southern Baptist church. White really loves these people. So while Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus tells us nothing new about the South and revels in its cliche, gothic images, thanks to Jim White, its heart is strong. l

For an excellent contemporary film about the South that gets at the ides of Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus without jumping through all the fancy hoops, I highly recommend Junebug. Tellingly, perhaps, the outsider in that film is English.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home