Coffee and Cigarettes (2003)

Coffee and Cigarettes (2003)

Director: Jim Jarmusch

I often think of Jim Jarmusch as the short story director. Among his "short story collections" are Night on Earth and Mystery Train. Even his more unified (and better) films, such as Dead Man and Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, have stories within the larger story that can be enjoyed in and of themselves. As writers know, short stories are hugely challenging, requiring extremely careful selection of details to sketch the entire mood and motivation of the action and actors. An episodic film also requires discipline and fortuitious choices, something that Jarmusch excels at when he's on. He misses, too, sometimes badly, as with the hopeless Night on Earth.

Coffee and Cigarettes is an episodic film shot over 17 years in which the vignettes are visually--not thematically--linked by having characters sitting in bars and restaurants smoking and drinking coffee (or, in two cases, tea). It is done in the best tradition of sketch comedy but with an actorly emphasis, and reminded me of an evening of one-act plays I saw at the Actors Studio. The atmosphere of an actors’ showcase and scene-study classes pervaded that evening, and pervades this film as well. This is not to condemn either event. I thoroughly enjoyed both my evening at the Actors Studio and even more thoroughly enjoyed Coffee and Cigarettes. I just make this note to prevent viewers from feeling the need to conduct a rather tortured formalist film analysis of the sort Jonathan Rosenbaum felt compelled to perform on this film in Chicago's The Reader newspaper.

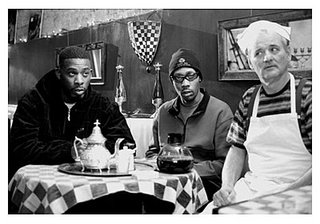

The film grew out of a request by Saturday Night Live to have Jarmusch make a short film for the show. The first episode, introduced (as all the subsequent short films in C&C are) with a title card, features SNL regular Steven Wright and Jarmusch regular Roberto Benigni speedy on espresso and barely able to understand their own conversation. It’s got art-house silly written all over it, a perfect parody of a show like SNL by Jarmusch. Subsequent segments of the film feature duets by musicians (Iggy Pop/Tom Waits; DZA/RZA of Wu-tang Clan), relatives (Cate Blanchett/"Cousin Shelly,” Blanchett, in a dual role; Alfred Molina/Steve Coogan [I know, I know, just watch the film]; Jack White and Meg White playing brother and sister; Joie Lee and Cinque Lee) and frequently paired actors (William Rice/Taylor Mead, Joe Rigano/Vinny Vella). The basic thematic link seems to focus on rivalries that eventually melt into camaraderie, but that’s as far as I wish to go in trying to find a unified field theory of this film. What Coffee and Cigarettes does best is make audiences laugh their asses off. Watching Bill Murray drink coffee directly from a coffee carafe is pure sight gag. The exchange between Alfred Molina and Steve Coogan is the most polished and most hilarious of the segments; it cracks open the sycophantic and emotionally needy actor stereotypes. Jarmusch gives the black-and-white cinematography he favors a bit of a goose when The Whites put on old-fashioned pilot goggles and watch a homemade Tesla coil crackle in an homage to the special effects used in Frankenstein. Blanchett is her usual brilliant self as a too-good-to-be-true version of herself and as her envious, neurotic cousin. Tom Waits apologizes to Iggy (“Call me Jim. Call me Iggy. Well, my friends call me Jim. Or Iggy.”) for being late to meet him because he had to perform roadside surgery. “You’re a doctor?” Iggy asks incredulously. “Oh yes. Music and medicine go together.” It’s priceless pretension.

What Coffee and Cigarettes does best is make audiences laugh their asses off. Watching Bill Murray drink coffee directly from a coffee carafe is pure sight gag. The exchange between Alfred Molina and Steve Coogan is the most polished and most hilarious of the segments; it cracks open the sycophantic and emotionally needy actor stereotypes. Jarmusch gives the black-and-white cinematography he favors a bit of a goose when The Whites put on old-fashioned pilot goggles and watch a homemade Tesla coil crackle in an homage to the special effects used in Frankenstein. Blanchett is her usual brilliant self as a too-good-to-be-true version of herself and as her envious, neurotic cousin. Tom Waits apologizes to Iggy (“Call me Jim. Call me Iggy. Well, my friends call me Jim. Or Iggy.”) for being late to meet him because he had to perform roadside surgery. “You’re a doctor?” Iggy asks incredulously. “Oh yes. Music and medicine go together.” It’s priceless pretension.

The film's monochromatic cinematography emphasizes the checkerboard table tops of many of the cafes in which shooting took place and reminds one of The Seventh Seal, as though something of great importance MUST be going on here. The film is a visual in-joke for film buffs, particularly those familiar with Jarmusch’s previous work. You’ll see a painting of Lee Marvin in one segment (the two marshalls in Dead Man are called Lee and Marvin in tribute to Jarmusch's hero), a cap embroidered with Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai in another. But you don't have to be a film buff to get it. Have a cup of java and see for yourself. l

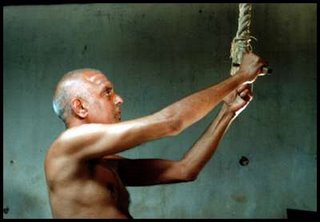

Wolf Creek (2005)

Wolf Creek (2005)

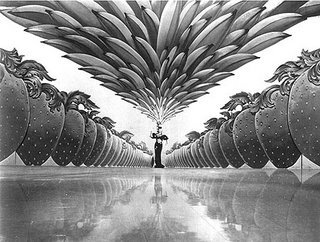

The Gang's All Here (1943)

The Gang's All Here (1943)