Wolfen (1981)

Wolfen (1981)Director: Michael Wadleigh

By Roderick Heath

1980-81 saw a revival of the werewolf flick, thanks largely to the explosion of special-effects technique, that Janus-faced friend of the horror film. Joe Dante and John Sayles’ The Howling and John Landis’s An American Werewolf In London sported set-piece transformation scenes achieved with prosthetics and gas bladders that were, at the time, startling and now just seem to bring those films’ narratives to a screaming halt. Michael Wadleigh’s Wolfen, not exactly a werewolf film, eschewed make-up or mechanical monstrosities for its villainy, and this is a problem. The real wolves used in Wolfen, pristinely furred and rather cute, are less threatening and unusual than the film’s admirably long build-up demands.

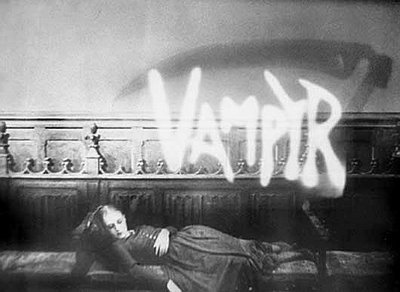

Wolfen was nonetheless hardly shy of utilizing then cutting-edge technology in constructing a genuinely modern horror film. Wadleigh used the newly invented Steadicam (also used in another great 1981 horror film, The Shining) and infrared cameras for POV shots (later stolen for 1986’s Predator), helicopter shots, and multilayered sound recording to create a vision of modern New York that is, in its way, as sophisticated and all-embracing as Dreyer’s style for Vampyr, but in an altogether different fashion. Wadleigh’s camera makes New York over as a kind of primal landscape, alien in its familiarity, sometimes surreally modern, and at other times a near-spectral space.

Where The Howling and An American Werewolf In London, sharp-witted films balanced by strong doses of fashionable gore, tapped into the self-satirizing, self-referential mood of their era and scored with audiences, the more ambitious and original Wolfen belly-flopped big time at the box office. As you’d expect from the director of Woodstock, Wolfen is a radical-spirited horror film (as opposed to films like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, where the counterculture are the victims, or The Last House On The Left, where they themselves are the horror). Based on a throwaway novel by new-age crank named Whitley Streiber, Wadleigh, displaying the same sweeping command of camera and editing as he did in his great concert film, creates a witty, if occasionally hectoring, thriller. Considering the allusions to Patty Hearst, the Weathermen, and Watergate, Wolfen must have seemed out of its time, and certainly against the grain of the oncoming Reaganite mood. With its insidious vision of omnipresent surveillance, environmentalist bent, and evisceration of corporate culture, Wolfen feels more contemporary now than it did at the time of its release. Wolfen’s use of modern forensic investigation also anticipates the fetishist ghoulishness of the CSI dynasty.

The film opens with two Native American men standing atop a Brooklyn Bridge arch, performing a rite. That night, one of the men, Eddie Holt (Edward James Olmos), throws a bottle at the passing limousine. In the limousine is Christopher Van der Veer (Max M. Brown) and his cocaine-sniffing wife (Anne Marie Pohtano). Later, this pair and their ex-Haitian secret police bodyguard/chauffeur are savagely killed by unseen beasts whilst visiting Van der Veer’s personal shrine, a windmill set up in Battery Park in honor of his ancestor, who founded the city. The police, and the omniscient security company that was watching over the Van der Veers, are mystified. Police Chief Warren (Dick O’Neill) calls in his ablest and most troubled detective, Dewey Wilson (Albert Finney), who has been suspended due to alcoholic binges after an unspecified personal trauma.

The film opens with two Native American men standing atop a Brooklyn Bridge arch, performing a rite. That night, one of the men, Eddie Holt (Edward James Olmos), throws a bottle at the passing limousine. In the limousine is Christopher Van der Veer (Max M. Brown) and his cocaine-sniffing wife (Anne Marie Pohtano). Later, this pair and their ex-Haitian secret police bodyguard/chauffeur are savagely killed by unseen beasts whilst visiting Van der Veer’s personal shrine, a windmill set up in Battery Park in honor of his ancestor, who founded the city. The police, and the omniscient security company that was watching over the Van der Veers, are mystified. Police Chief Warren (Dick O’Neill) calls in his ablest and most troubled detective, Dewey Wilson (Albert Finney), who has been suspended due to alcoholic binges after an unspecified personal trauma.Dewey is a mordant man with a shabby look and shabbier manner. He tramps through the investigation spurning bureaucracy (“The only thing separating you from a guard dog is a brain,” he tells a door-guarding officer, something I often quote to doormen loo

king for ID), keeps a sign on his office wall that reads “God, guns, and guts made America great; let’s keep all three,” and has a compulsion to make friends with all manner of oddballs and social rejects. Most prominent among them is his forensic expert pal Whittington (Gregory Hines, an obvious star in the making), and zoological expert and all-out geek Ferguson (Tom Noonan). These three, to the disdain and dismissal of the super-efficient security officials, happily drill away on their odd hunches involving wolf hair found on the Van der Veers and on scores of unidentified body parts found scattered all over Brooklyn. The security company investigates radical organizations they feel may have bumped Van der Veer off for his various acts of corporate monstrosity, including one to which Van der Veer’s niece belongs (“Revolutionary my ass!” a technician mutters, “Until her goddamn trust fund runs out.”).

king for ID), keeps a sign on his office wall that reads “God, guns, and guts made America great; let’s keep all three,” and has a compulsion to make friends with all manner of oddballs and social rejects. Most prominent among them is his forensic expert pal Whittington (Gregory Hines, an obvious star in the making), and zoological expert and all-out geek Ferguson (Tom Noonan). These three, to the disdain and dismissal of the super-efficient security officials, happily drill away on their odd hunches involving wolf hair found on the Van der Veers and on scores of unidentified body parts found scattered all over Brooklyn. The security company investigates radical organizations they feel may have bumped Van der Veer off for his various acts of corporate monstrosity, including one to which Van der Veer’s niece belongs (“Revolutionary my ass!” a technician mutters, “Until her goddamn trust fund runs out.”).Dewey is handed a partner by the company, Rebecca Neff (Diane Venora - why the hell isn’t that smart, sexy lady used more by filmmakers?), a psychologist with a particular interest into the mindset of revolutionary and antiestablishment movements. Neff (as Dewey insists on calling her) is a wry, skeptical match for Dewey. Dewey soon realizes how his forensic discoveries and the political angle may dovetail. He

tracks down Eddie Holt, an old acquaintance. Eddie, in his youth a hot-headed NAM member, assassinated an “apple,” a nonradical Indian leader. Eddie hints about shape-shifting, invoking the full revue of “Indian jive,” but ultimately reveals this as a humorous put-on that nonetheless hints at an unexplained meaning.

tracks down Eddie Holt, an old acquaintance. Eddie, in his youth a hot-headed NAM member, assassinated an “apple,” a nonradical Indian leader. Eddie hints about shape-shifting, invoking the full revue of “Indian jive,” but ultimately reveals this as a humorous put-on that nonetheless hints at an unexplained meaning.Dewey and friends have latched onto the trail of the Wolfen – a super-intelligent species of wolf closely linked to the native humans, who have, like Eddie’s tribe, survived not by running from civilization but by burrowing within its bowels. Now that their hunting and breeding grounds in the slums of New York are threatened, they’ve retaliated directly by killing the mastermind. Eddie and his fellow Indians know of the Wolfen and mock Dewey as an inadequate representative of white America. Dewey and the Wolfen begin their mutual stalking. The Wolfen kills the animal-loving Ferguson when he misunderstands their appearance, and refrain from attacking Dewey and Neff in bed for the sublimely animal reason that killing a

breeding pair seems, for them, to be verboten. Dewey and Whittington patrol the Wolfen’s apparent nest – a gorgeously spooky, shattered church – with high-powered rifles, but find themselves outmatched. After a conflict that costs the lives of Whittington and Warren, including a battle that pointedly takes place on Wall St. and ends in flame and bloodshed, Dewey, finally deducing the Wolfen’s motives, signals to them his understanding by smashing Van der Veer’s model of the ultramodern buildings to be erected on their home turf.

breeding pair seems, for them, to be verboten. Dewey and Whittington patrol the Wolfen’s apparent nest – a gorgeously spooky, shattered church – with high-powered rifles, but find themselves outmatched. After a conflict that costs the lives of Whittington and Warren, including a battle that pointedly takes place on Wall St. and ends in flame and bloodshed, Dewey, finally deducing the Wolfen’s motives, signals to them his understanding by smashing Van der Veer’s model of the ultramodern buildings to be erected on their home turf.Despite being the biggest-budgeted film I’ve reviewed in my horror series – or because of it – Wolfen is the least forgivably uneven. But Wadleigh’s approach is so vigorous and original that you want to forgive his lapses into trite sermonizing and Green-leftie imagery about as deep as the weeping Indian ad, especially in the faltering coda that also hints at an already dismissed supernatural side to the Wolfen. With clever, consistent visual layering, Wadleigh evokes an eerie, alternate universe, showing how the Wolfen’s awesome senses work. The surveillance and lie detector gear the security firm spend a fortune on and the

arduous forensic work that Whittington performs, do jobs the Wolfen perform naturally. In the film’s bravura sequence, accompanied by James Horner’s unnerving, exciting score (back when he still did exciting scores), a Wolfen tracks Dewey and Neff from Brooklyn to Manhattan, deducing barely visible tire tracks and intangible scents, crossing the Brooklyn Bridge, casually killing a hardhat, and crossing the span – guy wires glowing in hallucinogenic beauty to the Wolfen’s eye. As evidenced by this sequence the cinematography, by Gerry Fisher, Fredric Abeles, and Steadicam inventor and operator Garrett Brown, is often astonishing.

arduous forensic work that Whittington performs, do jobs the Wolfen perform naturally. In the film’s bravura sequence, accompanied by James Horner’s unnerving, exciting score (back when he still did exciting scores), a Wolfen tracks Dewey and Neff from Brooklyn to Manhattan, deducing barely visible tire tracks and intangible scents, crossing the Brooklyn Bridge, casually killing a hardhat, and crossing the span – guy wires glowing in hallucinogenic beauty to the Wolfen’s eye. As evidenced by this sequence the cinematography, by Gerry Fisher, Fredric Abeles, and Steadicam inventor and operator Garrett Brown, is often astonishing.Wadleigh called the film “the thinking man’s horror film,” which is a bit arrogant and easy to ridicule. But the film’s linkages of image and idea are deliberate and rich. Much of the drama revolves around the Brooklyn Bridge, that neo-Gothic link between history and the future, architecture and art. Van der Veer, scion and descendent of a founding family with a shrine of humble beginnings at Battery Park, is a “real friend of the Third World” in Dewey’s sarcastic appraisal, funding government overthrows and the like; he is the oldest, purest incarnation of the invading European exploitation of North America, whilst, as Ferguson describes it, the Indians and the wolves went on the “genocide express,” yet they survive through cleverness. The Wolfen scavenge on the people society allows to be thrown away – the sick, the homeless, the junkies. The movie’s suggestion that urban renewal, supposedly a way of improving the living standards of poor, inner city populations, but actually a device to force them out and usher in gentrification and the destruction of authentic identities, has been proven dead right. Ultimately, Wadleigh, with a certain upbeat charm, suggests the wild, the natural, and the oddball will always beat out the technological, the repressive, and the corrupt.

The messages of Wolfen ultimately hardly matter more than the conservative Catholicism of The Exorcist; they’re both just well-staged yarns. Wolfen delivers through the byplay between Finney, Hines, and Venora, which is humorous and intriguing, and tramples the cliché aspects of Dewey’s outsider cop, Neff’s spunky gal pal, and Whittington’s streetwise black dude headed for a sticky end. Most of the film is a model of careful build-up, sustained mood, and judicious violence. It’s a true pity Wadleigh has not made another film, but he did forge a style that would be exploited by future blockbuster directors.

But I still want to give the Wolfen a scratch behind the ear. l

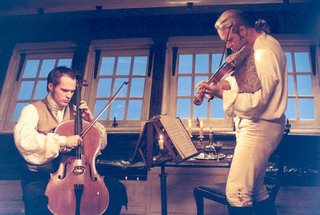

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003)

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003)

Vampyr: Der Traum des Allan Grey (1931)

Vampyr: Der Traum des Allan Grey (1931)

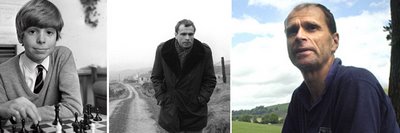

49 Up (2005)

49 Up (2005)

together, though, and got into politics at the city council level in London. Now, still single and still battling problems being around people, he moved back to Scotland, is running for office again as a liberal in a conservative rural district, and is active in the Anglican church. I can tell you that I and other Up followers were relieved to find out in 42 Up that he was still alive, and I’m delighted that he’s still hanging in there.

together, though, and got into politics at the city council level in London. Now, still single and still battling problems being around people, he moved back to Scotland, is running for office again as a liberal in a conservative rural district, and is active in the Anglican church. I can tell you that I and other Up followers were relieved to find out in 42 Up that he was still alive, and I’m delighted that he’s still hanging in there.