Detour (1945)

Detour (1945)Director: Edgar G. Ulmer

Detour, a $30,000 quickie produced in 6 days by a no-name film company and a B movie director, is considered a classic film noir - perhaps the earliest pure example of the form - that is essential viewing for any film buff. To see this film for the first time is to fight competing impulses: laughter at its many technical "mistakes" and uneasiness over the snowballing "bad luck" of the protagonist, Al (Tom Neal). Neither impulse is wrong, but both are more complicated than they seem. Detour is the perfect name for a film that takes its audience far from its usual expectations to realize, only slowly, that they are riding along with a psychopath.

Al narrates the film from beginning to end. When we first meet him, he’s playing piano with a small combo in a low-rent nightclub in New York City. His girl, a pretty blonde named Sue

(Claudia Drake), is the combo’s singer, and she has a great voice. One evening, he is playing solo on stage, embellishing on classical themes in a truly masterful way. The manager comes up to him and hands him a $10 tip from a patron. He’s scornful of this tip: "When this drunk gave me a ten spot, I couldn't get very excited. What was it? A piece of paper crawling with germs." Al thinks he should be in the big time, playing Carnegie Hall. When he shares his bitterness with Sue, she is sympathetic but is worried about her own dreams of success. She has decided to go to Los Angeles and try her luck out there. We watch them walk down a foggy street to her apartment; in one of the many technically clumsy moments, the street is so fogged up by an overzealous technician that we can’t see them at all for part of the walk. She tells him they can still get married as they planned, but just not for a while.

(Claudia Drake), is the combo’s singer, and she has a great voice. One evening, he is playing solo on stage, embellishing on classical themes in a truly masterful way. The manager comes up to him and hands him a $10 tip from a patron. He’s scornful of this tip: "When this drunk gave me a ten spot, I couldn't get very excited. What was it? A piece of paper crawling with germs." Al thinks he should be in the big time, playing Carnegie Hall. When he shares his bitterness with Sue, she is sympathetic but is worried about her own dreams of success. She has decided to go to Los Angeles and try her luck out there. We watch them walk down a foggy street to her apartment; in one of the many technically clumsy moments, the street is so fogged up by an overzealous technician that we can’t see them at all for part of the walk. She tells him they can still get married as they planned, but just not for a while.Al is torn up by Sue’s departure. One night, he phones her from a pay phone. We only get his side of the conversation and a 2-second cut-in of Sue to prove, I guess, that he really is talking to her. This was done, no doubt, to save money on film. He’s coming out to be with her if he has to hitch the whole way—and he very nearly does. We are shown one of those cheesy maps that marks his progress across country and watch him thumbing along the highway. Someone had the bizarre idea to show Al traveling from right to left across the movie screen to simulate a westward journey. To achieve this unnecessary effect, the film was flopped, so it appears that all the cars Al gets into have their steering wheels on the right side of the car. When he finally gets into a car in Arizona that has the steering wheel where American cars ought to have them, the noir part of the story really takes root.

In Arizona, Al is picked up by a man named Charles Haskell, Jr. (Edmund MacDonald), a professional gambler on his way to L.A. from Florida. Haskell’s got a fancy convertible car, a roll of cash, a generous disposition, and, apparently, a heart condition; he asks Al to give him a box of pills from the glove compartment from time to time that must contain nitroglycerine. Al notices a nasty gash on Haskell’s hand that looks like he was mauled by a wildcat. Haskell says it was a wildcat but not an animal. It was a dame with a 100 percent mean streak running through her.

The two men take turns driving. One night while Al is driving, it starts to rain. Al stops the car to put up the top. He asks Haskell to move aside as he reaches for the top on the passenger side, but Haskell doesn’t respond. Al opens the door, and Haskell spills out onto the ground, apparently dead of a heart attack. Al panics. He fears the cops won’t believe a penniless hitchhiker like him that Haskell died of natural causes. He ditches Haskell’s body in some bushes, takes his clothes to look more respectable, and takes his wallet and identity.

The next day, Al pulls up at a filling station. He notices a young woman hitching near the station and offers her a ride. He seems to find her an odd sort of attractive. She says her name is Vera (Ann Savage), but doesn’t offer up much more information. He says his name is Haskell. They ride for a while, and finally, she turns toward him with a ferocious look on her face. She says, “You’re not Haskell!” She was the woman who scratched Haskell, and she assumes Al has probably killed him. From that moment on, Al is her prisoner, forced to take care of her so she won’t turn him into the police. They move into an apartment in L.A. Al intends to sell the car he took off Haskell and give Vera the money to pay her off.

The next day, Al pulls up at a filling station. He notices a young woman hitching near the station and offers her a ride. He seems to find her an odd sort of attractive. She says her name is Vera (Ann Savage), but doesn’t offer up much more information. He says his name is Haskell. They ride for a while, and finally, she turns toward him with a ferocious look on her face. She says, “You’re not Haskell!” She was the woman who scratched Haskell, and she assumes Al has probably killed him. From that moment on, Al is her prisoner, forced to take care of her so she won’t turn him into the police. They move into an apartment in L.A. Al intends to sell the car he took off Haskell and give Vera the money to pay her off. Unfortunately, she sees an item in the paper that says that authorities are looking for the long-lost heir to the fortune of Charles Haskell, Sr. Vera insists Al try to impersonate Haskell and collect on the fortune. Al protests he'll never pull it off - he couldn't even tell the manager at the car dealership what kind of insurance he carried on the car when he tried to sell it. A very drunk Vera makes good on her threat to phone the police. She dials, but the call is never completed. Al accidentally kills her in a rather ingenious scene.

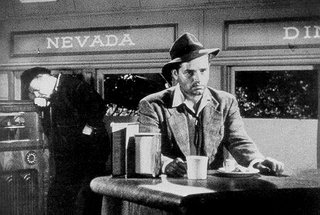

When we next see Al, he's sitting in a diner on his way back East, dreaming of Sue and pleading with the audience to believe that things just don't work out for him: "Yes. Fate, or some mysterious force, can put the finger on you or me for no good reason at all."

When we next see Al, he's sitting in a diner on his way back East, dreaming of Sue and pleading with the audience to believe that things just don't work out for him: "Yes. Fate, or some mysterious force, can put the finger on you or me for no good reason at all."There are a number of elements that make this film work. First, Ann Savage lives up to her name. She plays Vera as a spiteful survivor, quick to make threats and even quicker to carry them out. She’s utterly mesmerizing to watch as the first real noir femme fatale who uses her wits to manipulate a seemingly weak man. The script is beautifully written by Martin Goldsmith based on his own novel. It's hardboiled without being one long cliche, colorful without drawing too much attention to itself. These characters could have said these things, which is not something you could ever say of another supplier of noir material - Mickey Spillane.

What really makes this film fascinating is Al's first-person narrative. This is the film that taught me an unforgettable lesson about the unreliable narrator. If we hadn't had the voiceover from Al's point of view, we would be inclined to think he was a true innocent caught in a spiral of bad luck and fear. Instead, we are forced to examine every element of the film to see if it seems plausible, to see if maybe it didn't happen another way. Was Al's musicianship as great as we heard, or was it what he imagined? If he really was the next Paderewski, as his boss snidely suggests, would he really be playing in a dump?

Let's look at Sue's departure. He says they were to be married. To me it looks like a classic brush-off. You don't move across country to keep a relationship going. Perhaps the cut-in of Sue wasn't just a cheap effect. Maybe his entire conversation was a fantasy. Every aspect of this film has to be questioned from an objective standpoint, and that's what makes it such an object lesson in audience manipulation. Even the cheap look contrasts the tawdriness of Al with his vision of himself. That most likely was unintentional, but it happens nonetheless.

I love Detour. It's the model for Memento, Secret Window, and every other film that tries to make a viewer believe it's something it's not, and may even succeed whether we ought to or not. l

1 Comments:

At 10:58 AM, Detour Movie said…

Detour Movie said…

"Detour" was shot in two sets and it shows. It's a small film that doesn't pretend what it's not, and that's basically why audiences seem to like it as it's discovered.

Post a Comment

<< Home