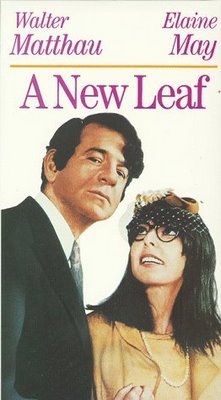

A New Leaf (1971)

A New Leaf (1971)Director: Elaine May

As a Chicago native, I feel a particular kinship with Elaine May. As the female of half of the comedy team Nichols & May, she helped forge a peculiarly Chicago style of humor based on improvisation that has been exported around the world by alumni of the comedy group, the Compass Players, and its offshoot, Second City. Both Nichols and May went on to careers as film directors in Hollywood, but only Mike Nichols has been able to sustain that career. Elaine May's fourth film, Ishtar (1987), laid such an egg that she never got to sit in the director's chair again. Luckily, we have her debut film, A New Leaf, one of the funniest films I have ever seen.

A New Leaf opens by introducing us to Henry Graham (Walter Matthau), a fussy, middle-aged bachelor who has been living off a trust fund as a brahmin in elite New York society. He rides, he drives a Ferrari, he goes to his club, and he employs a manservant named Harold (George Rose), embracing "a tradition that was dead long before you were born." He's snobbish, foppish, and very nearly broke.

Henry does not realize he's about run out of money until a bounced check is returned to him. He confronts Beckett, his banker (Mike Nichols lookalike William Redfield), about this embarrassment and outrage. In classic Nichols & May style, Beckett tries to explain to Henry that his trust fund could have afforded him a living of $70,000 a year, but that he chose to spend $200,000 a year. As a consequence, Henry has blown through his trust fund. He no longer has any money. Henry sits looking at Beckett in a defiant, but quizzical way. He responds, pointing to the piece of paper in contention, "What about this check?" Beckett explains that he just explained that Henry hasn't any money. "But no check has ever bounced before," Henry offers, apparent proof that he is not without money. Beckett says that Henry has indeed bounced checks before. "I have covered them, $545 of my own money, just so that I might never have to meet with you." Beckett considers it a bargain, too. When the news finally seems to reach Henry's vacuous brain, he pulls together as much dignity as possible and offers Beckett his gold cigarette case, dumping its contents onto Beckett's desk. "This should cover the $545 I owe you. Smoke them in good health."

In despair, Henry seeks Harold's consolation. He asks Harold what he would do if Henry couldn't pay him anymore. "I should leave immediately - after giving proper notice, of course." So much for consolation. He tries for counsel. Harold suggests asking Henry's rich uncle for a loan. Uncle Harry (James Coco) did, after all, raise the orphaned Henry. This, of course, was a laughable suggestion when Henry first made it to Beckett. Uncle Harry hates Henry's guts. Henry is coming to the conclusion that the only thing left is suicide, that is, until Harold suggests that he marry money. Henry grasps at this hopeful straw while, at the same time, finding repugnant the idea that someone would come in and touch his things. Henry, it appears, is completely asexual and perhaps afflicted with a mild case of obsessive-compulsive disorder. How will he pull it off? He decides he can manage it only if he does away with his bride soon after appropriating her fortune.

Henry practices humbling himself to his uncle to obtain a $50,000 loan to keep up appearances while he woos and wins an appropriate female. He goes to his even more fey and disagreeable uncle, who laughs at his suggestion. Henry offers him an interest rate and 6-week term that would have made Shylock blush. Uncle Harry considers and then makes a counter offer. He will accept Henry's terms, but if Henry does not repay the debt with interest on time, Uncle Harry will be entitled to 10 times the initial loan - all that Henry has left. Henry is so desperate to remain idly rich that he agrees. He immediately sets about his task.

He attends a garden party, where a rich woman named Sally Hart (Renée Taylor) is pointed out to him. He takes her aside, and they sit under tree as Henry swats mosquitoes on his neck and face and Sally writhes seductively in his direction. As she appears ready to remove her top, the camera closes in on her cleavage. We hear Henry's anguished cry of "Don't let them out!" Strike one.

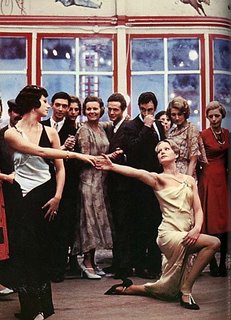

Henry's further attempts are fruitless. With only a little over a week to go, he goes to his tailor to bid him adieu. He enters Lutece to see its elegant dining room once more. In a never-say-die moment, he attends a luncheon where a likely prospect finally pops up. She is a wallflower named Henrietta Lowell (Elaine May), a botanist and university professor who is heir to a fortune. "Who was her father?" Henry asks his friend Bo (Graham Jarvis). "He was an industrialist or a composer. Something like that." Henry approaches her. She spills tea all over the oriental rug. The maid starts to blot the rug. She spills another cup of tea. Her hostess accuses Henrietta of maliciousness. Henry expresses outrage on Henrietta's behalf - and the courtship is on.

He instructs himself on the finer points of botany like a man possessed. Henrietta asks him if he is a botanist, too. Oh no, he assures her, "Every science has its fans." He seeks to get to know her better:

"Tell me about yourself, Miss Lowell - your work, your hopes, your dreams."

"Well, I work as a teacher, and I also do field work and write monographs. My hope is to discover a new variety of fern that has never been described or classified. I don't know what my dream is. Do you think it could be the same as my hope? Well, at any rate, that is my work and my hope except for my dream, which I'm not sure of."

He takes her to dine and expounds on the relative merits of a '55 wine over a '56 vintage. Henrietta interjects that she never liked alcohol until one of her students introduced her to a drink on one of their field trips. "Have you ever tasted Mogen David extra-heavy malaga wine with soda water and lime juice?" No, but he will. He'll do anything to marry this woman in time.

Henry proposes three days after their meeting, and she accepts. Her lawyer Andy (Jack Weston) is beside himself. He has been controlling her money for decades - and thieving from her along with the rest of her large household staff - and doesn't want anyone else milking his cash cow. He tells her about Henry's $50,000 debt as proof of his fortune hunting. Henry confesses that he was suicidal about his financial condition - until he met her. Henrietta decides to settle Henry's debt and give him full access to her fortune to prove he is not after her money. OK, yeah, did you follow that? Me neither.

While they are on their honeymoon, Henrietta leans dangerously over a cliff to collect a fern she doesn't recall having encountered before. They return to her palatial estate, and Henry plots her demise, seeking out household gardening products to use in a lethal brew. Unfortunately, Henrietta believes in organic gardening. Rats! He must devise some other means, but in the meantime, he throws himself into running her house and taking care that she is not an embarrassment to him:

"Oh, no. I forgot to check her before she went to school this morning. She'll be walking around all day with price tags dangling from her sleeves."

"I took the liberty, sir."

"Thank you, Harold. Was she free of crumbs?"

"Only a slight sprinkling, sir."

Harold is becoming rather fond of the pathetically endearing Henrietta and tries to dissuade Henry from what he fears he will do to her. But Henrietta herself may inspire Henry to a change of heart when she joyfully announces that she has discovered a new fern and has named it after him in gratitude for the confidence he instilled in her to pursue her hope (or dream?). He seems genuinely touched that she would give up her place in history to him. But then they go on a botanical expedition alone, and his scheme has its best chance to succeed.

A New Leaf is graced with a raft of comedy's finest practitioners bringing to life one of its finest scripts. I'm reasonably sure that many parts of this movie came about through improvisation of an order that comedians working today can only envy. In addition, the physical humor, particularly as provided by Elaine May, has me rolling on the floor just thinking about it.

I have wanted to see this comedy again for years, but it is surprisingly hard to find. If the hubbie had not been so persistent on eBay to secure us an old VHS recording, I wouldn't have spent my holiday laughing my ass off. This, like The Conformist, is another superb, sophisticated movie that Paramount, in its infinite wisdom, has taken its sweet time releasing on DVD. I'll be writing to them to see if I can help pry it loose. I hope you will, too. l

Write to Paramount Home Video, 5555 Melrose Ave., Hollywood, CA 90038, U.S. Start by thanking them for releasing The Conformist. A little appreciation goes a long way.

Detour (1945)

Detour (1945)